June 05, 2024 | Holly Moody-Porter

Clinical Trial Finds Oral Medication Significantly Reduced Prurigo Nodularis and Chronic Pruritus of Unknown Origin Symptoms

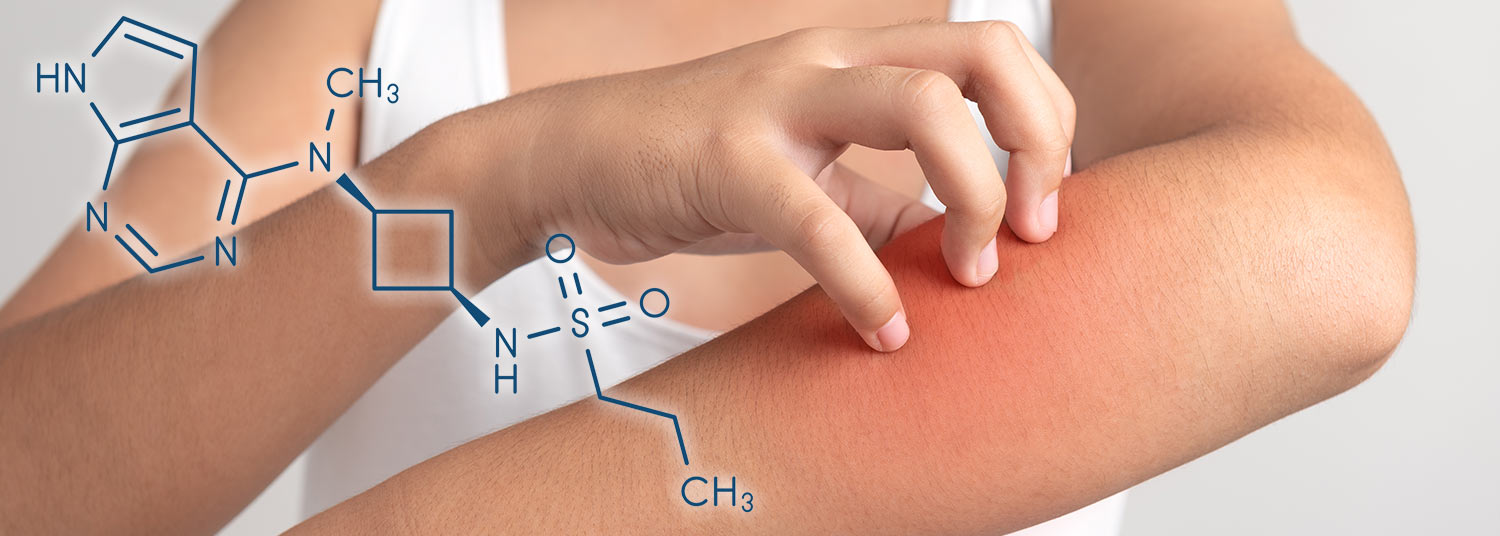

A drug approved to treat eczema provided significant improvement in the symptoms of patients with severe itching diseases that currently have no targeted treatments, according to a new study published in JAMA Dermatology. The drug, abrocitinib, was found to cause minimal side effects during a small 12-week study led by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers. It was beneficial for those with an itching disease called prurigo nodularis as well as for those with chronic pruritus of unknown origin, a condition that causes chronic unexplainable itching symptoms. “Very few treatments exist for prurigo nodularis and chronic pruritus of unknown origin; patients often suffer for years in horrible discomfort, which can lead to anxiety and depression, severely impacting their quality of life,” said Shawn Kwatra, MD, the Joseph W. Burnett Endowed Professor and Chair of Dermatology at UMSOM and Chief of Service Dermatology at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC). “The rationale for this study came from my laboratory’s studies findings of altered inflammatory mediators in these conditions that all function through JAK1. Through this trial, we hope to continue to move the needle toward personalized therapies that can provide sustainable relief for coping with these debilitating conditions.”

“Very few treatments exist for prurigo nodularis and chronic pruritus of unknown origin; patients often suffer for years in horrible discomfort, which can lead to anxiety and depression, severely impacting their quality of life,” said Shawn Kwatra, MD, the Joseph W. Burnett Endowed Professor and Chair of Dermatology at UMSOM and Chief of Service Dermatology at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC). “The rationale for this study came from my laboratory’s studies findings of altered inflammatory mediators in these conditions that all function through JAK1. Through this trial, we hope to continue to move the needle toward personalized therapies that can provide sustainable relief for coping with these debilitating conditions.”

Affecting at least 130,000 Americans, prurigo nodularis causes dozens of extremely itchy and disfiguring bumps, usually on the chest, arms, and legs. Dr. Kwatra’s previous research indicates that prurigo nodularis occurs more than 3 times as frequently in Black patients than white patients, tends to be more common in women, and is associated with depression, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and HIV. Chronic pruritus of unknown origin is most prevalent among older adults and causes severe itching lasting longer than six weeks. Current therapies used to help manage symptoms include over-the-counter and prescription itch relief ointments and anti-inflammatory drugs such as antihistamines and corticosteroids. None of these medications, however, provide sustained relief.

The study involved a total of 20 patients, half of whom had prurigo nodularis and half of whom had chronic pruritus of unknown origin. They were all given a 200-milligram pill of abrocitinib once a day for 12 weeks; the patients knew they were being given an experimental treatment, and the study did not include a placebo group. Abrocitinib was found to reduce itching and pain symptoms by 78 percent in the prurigo nodularis patients. Patients with chronic pruritus of unknown origin experienced a 54 percent reduction in itching and pain symptoms. Patients in both groups also reported an improvement in their quality of life and in their sleep habits.

None of the patients experienced serious adverse events. The most common side effect, in 10 percent of patients, was small acne-like bumps.

Abrocitinib is a JAK1 inhibitor drug that works to suppress inflammation, specifically pro-inflammatory chemicals called cytokines that are involved in an overactive immune system. The drugs appear to slow down immune activity by suppressing intracellular signaling of these cytokines.

“This is not only an encouraging study but also sets the stage for a Phase 3 clinical trial,” said Mark T. Gladwin, MD, who is the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean of UMSOM, and Vice President for Medical Affairs at University of Maryland, Baltimore. “It holds promise for introducing a novel treatment to patients in underserved communities disproportionately affected by prurigo nodularis, a condition historically overlooked by dermatology.”

“This is not only an encouraging study but also sets the stage for a Phase 3 clinical trial,” said Mark T. Gladwin, MD, who is the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean of UMSOM, and Vice President for Medical Affairs at University of Maryland, Baltimore. “It holds promise for introducing a novel treatment to patients in underserved communities disproportionately affected by prurigo nodularis, a condition historically overlooked by dermatology.”

Since beginning his position at UMSOM, Dr. Kwatra has created the Maryland Itch Center at UMMC and is currently continuing his research there.

Study co-authors included faculty from Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, and The George Washington University.

Pfizer, Inc., manufacturer of abrocitinib, provided funding (as well as the drug) for the study. When employed at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Kwatra served as a paid consultant for Pfizer and, he is also funded by the National Institutes of Health.

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Now in its third century, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world -- with 46 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs, and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished two-time winner of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1.2 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic and clinically based care for nearly 2 million patients each year. The School of Medicine has nearly $600 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total population of nearly 9,000 faculty and staff, including 2,500 students, trainees, residents, and fellows. The combined School of Medicine and Medical System ("University of Maryland Medicine") has an annual budget of over $6 billion and an economic impact of nearly $20 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine, which ranks as the 8th highest among public medical schools in research productivity (according to the Association of American Medical Colleges profile) is an innovator in translational medicine, with 606 active patents and 52 start-up companies. In the latest U.S. News & World Report ranking of the Best Medical Schools, published in 2021, the UM School of Medicine is ranked #9 among the 92 public medical schools in the U.S., and in the top 15 percent (#27) of all 192 public and private U.S. medical schools. The School of Medicine works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu.

Contact

Holly Moody-Porter

Sr. Media & Public Relations Specialist

hmoody@som.umaryland.edu

Related stories

Wednesday, August 14, 2024

Patients with Unexplainable Chronic Itch Have Unique Blood Biomarkers that Could Eventually Lead to New Targeted Treatments

Millions of patients worldwide suffer from a chronic itching condition with no identifiable cause – a condition known as chronic pruritus of unknown origin (CPUO) – that has no targeted therapies approved to treat it. Many of these patients suffer for years with little relief, but a new University of Maryland School of Medicine study may provide hope for future treatments. Patients were found to have lower than normal levels of metabolite biomarkers in the blood plasma that could point to a cause of their excruciating symptoms.