The UMB Post[doc]

July 2020

Do Race and Ethnicity Define Your Health?

Tackle Inequality in America by Teaching Racially Diverse Signs and Symptoms of Disease

SPOTLIGHT ON: Dr. Natalie D. Eddington, Dean, UMB School of Pharmacy

Racial Disparity in Grant Funding and What We Can Do

July Career Development Events

Introduction

Welcome to the second issue of The UMB Post[doc].

In our first issue, we focused on science, professional development, and vaccine research in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the virus continues to disrupt our everyday lives, another critical issue has come to the forefront - racial inequity in our society. However, unlike SARS-CoV-2, the problems of racial injustice and inequalities are not new.

In this issue, we focus on racial inequity, particularly of Black Americans, in academia and science. We reached out to members within the UMB community who generously gave us their time, shared their experience, and answered our questions on how to navigate conversations about race and diversity.

We hope this issue of the newsletter can help us all consciously consider the inequities within our immediate context and strive to address them.

Thank you for reading.

The UMB Post[doc]

An Interview with Dr. Alicia Howard - Addressing Social Disparities and Diversity at the University of Maryland Baltimore

Tramy Hoang

Current events in our country have highlighted a long-standing challenge facing Black Americans. What has become clear is that racism permeates every aspect of American life and culture, from medicine to law enforcement, and sports to education, and many more. Baltimore is no stranger to racial injustice. The Roland Park neighborhood has its origins based on racial restrictive covenants aimed to keep Black Americans out. In 1910, Baltimore passed the first residential segregation ordinance in the United States. While this ordinance did not last, it led the way to the practice of “red-lining” which indicated areas too risky for mortgage loans (mostly majority-Black neighborhoods). Today, we are still one of the most segregated cities in the country and, while our city’s population is predominantly Black (62.7 percent), they fare worse than the average Black American. Housing segregation is one of the major factors contributing to the racial inequalities experienced by Black Americans. In the continued fight against racial inequities, Baltimore is on the right track with the passing of two bills (in 2019) that acknowledged “institutional and structural racism within governing” and added policies, funding, and resources to address racial disparities. While this is a good start for our city, there is much more work to be done by organizations and individuals alike.

What can we do? How can we help? The University of Maryland Baltimore has a long list of organizations, many student run, with various political and cultural focuses. In this article, we feature Dr. Alicia Howard, a post-doc in the School of Pharmacy who serves as a council member for the UMB Diversity Advisory Council (DAC). Through this interview with Dr. Howard, we hope not only to get to know a fellow post-doc but find some inspiration on ways that we can get involved in our community, both here at UMB as well as our larger Baltimore community.

Dr. Howard is from Baltimore and studied Molecular and Cell Biologyat Hampton University (B.S.) and UMBC (Ph.D.). She is currently a post-doc whose research investigates the role of DYRK1B nuclear kinase in cardiometabolic physiology. She is pursuing a career in regulatory affairs.

What are some of your hobbies and interests?

I enjoy helping people, so I volunteer for science fairs, community outreach events and a women's shelter. I am active in my high school and college alumni associations which afford me opportunities to participate in service projects. I absolutely adore animals so I enjoy spending time with my dog and cats. I guess I would say I have been in search of a hobby. Because I have not found any one thing I enjoy, I am constantly trying something new through meet up groups or with organizations.

What lead you to come to UMB for your graduate and post-graduate training? What kind of environment did you find here (in terms of mentorship, support, and diversity)?

I came to UMB because I wanted [to] stay local (I am a Baltimore City native), and I wanted to transition into biomedically-centered research. The first lab [I] joined provided me the opportunity to apply the molecular and cell biology skills I obtain through my graduate work.

I can’t thank Renee Cockerham, PhD and Jennifer Aumiller, MEd enough for the work they have done to ensure that I get the most out of my postdoc experience. I am also thankful to the PDAC for providing a sense of community. The coffee and happy hours improved my well-being.

I guess it depends on how you define diversity, but the number of people who look like me in the scientific research community is low. This is certainly not unique to UMB and I applaud the University’s efforts to make the campus more equitable and inclusive, while acknowledging we still have quite a way to go. The President’s Diversity Advisory Council is one example of the University’s commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion and I have also attended several events sponsored by the office of Interprofessional Student Learning & Service Initiatives (ISLSI). ISLSI provides excellent social and cultural learning opportunities that promote cultural competence. Additionally, UMB will have an Intercultural Leadership and Engagement Center which builds on the work ISLSI has done.

Did you seek out mentors or wanted to seek out mentors who could better understand the unique challenges of race-based experiences? Do/did you have any mentors that have been particularly impactful in your life and/or career?

I did not seek out mentors who, specifically, could better understand the unique challenges of race-based experiences. Oftentimes when a person presents as “diverse”, they become all things diversity and are already bombarded with mentees.

I have received excellent support from my current mentor, Simeon Taylor, MD, PhD. He has helped me to become more confident in my knowledge and abilities and more vocal when it comes to advocating for myself.

Could you tell us more about the Diversity Advisory Council and your involvement? What are some achievements and positive changes that the council is proud of? What are some short- and long-term goals of the council? Have you found the University and the administration to be supportive of DAC and its plans and visions?

I have been on the DAC for five years. The Council meets once a month (usually with the president if his schedule permits) except for July and December. We discuss diversity, equity, and inclusion related to campus climate and current events and provide the president with recommendations regarding the issues. The DAC also sponsors a Diversity Speaker Series, co-sponsors and/or promotes diversity related events on campus and has created Faculty and Staff Affinity Groups. Since joining I have participated in various trainings. When I started, I worked on the bylaws committee. I have also served on the committee to select winners for the annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Black History Month Celebration. The committee I have served on the longest is the Communications and Marketing Committee. Through this committee I have done regular tabling events to promote the DAC at campus events including open houses. During monthly meetings I help evaluate the messaging on the DAC website and discuss ways to recognize diversity and inclusion efforts campus wide.

I do believe the University and administration are supportive of DAC and its recommendations. Our recommendations have been agenda items for meetings between the president and school deans and have been incorporated into the University’s Strategic Plan.

Members of the Council are appointed by the president and it would be great if PDAC wants to nominate a representative!

As for your volunteering work with CURE, can you tell us about that experience? What did you gain from that experience? What do you think of CURE and its goals and achievements so far?

I have served as a judge for the CURE Stem Expo. I have also participated in programming for Maryland STEM Day. My experience has been great! The participants are always excited to showcase their knowledge, and the families are enthusiastic as well. I have always felt like I never have quite enough time to discuss their projects with them.

I think CURE is an excellent program and an example of UMB’s commitment to inclusivity, starting with the people in its own neighborhood. It is a pipeline program intended to increase diversity in STEM. It meets children where they are and is not all about grades, but about a desire to learn about science. The program recognizes that while many children in West Baltimore may lack opportunity (largely due to the legacy of racism and practices of Redlining), they are not lacking in ability. The program has met its initial goals. The early cohorts are now in high school and they continue to receive mentorship through a new program CURE Connections (C2). For these programs to fully reach their goals, they need to continue to recruit mentors and would love to have more postdoc mentors. If full-time mentoring is too much of a commitment, postdocs can contact the CURE office to learn of other ways to get involved.

Being a successful research scientist and a woman of color - what advice do you have for female and under-represented minority students and postdocs? What advice do you have for allies who want to make academia a more inclusive environment for everybody?

My advice is to seek individuals and mentors who are committed to your success, and with whom you feel comfortable with having uncomfortable (race- and gender-related) conversations. The value of these relationships becomes increasingly evident as you continue to encounter microaggressions and unforeseen events unfold.

For those seeking to create a more-inclusive environment, I think it is important to “see race” and/or to acknowledge differences (race, sex, culture, ethnicity, etc.) without simply labeling someone as “other”. I also think it is extremely important to have empathy and to acknowledge that, while you personally may not have had a similar experience, the pain marginalized individuals feel is very real.

In 2010, underrepresented minorities make up 29.3 percent of the US population. However, they only account for 14.7 percent and 8.3 percent of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) bachelor’s and doctorate degrees (respectively). The UMB CURE Scholars program aims to address this disparity in our own neighborhood by partnering with three local Baltimore City Public Schools to encourage and provide mentorship and hands-on experience to 6th-12th grade students to help them explore and pursue an education and career in a STEM field. The program is always looking for mentors and provide many ways in which to mentor. Visit their website to learn more about the program and how to become a CURE mentor or volunteer.

A report by the US Department of Education found that racial and ethnic disparities are more apparent at the postsecondary level, which further extends into the work place. The UMB DAC works with the President to promote the “University’s commitment to diversity, inclusion, and equity”. To learn more about their goals and initiatives, visit their website. There is also a tremendous amount of resources covering different aspects of diversity and inclusion, as well as tools and support for those who need it.

Dr. Howard also mentioned the Interprofessional Student Learning & Service Initiatives (ISLSI)whose mission is to provide students with opportunities that promote “community engagement and social responsibility.” Visit their website to learn more about some of their programs and initiatives such as the Poverty Simulation, The Don’t Cancel Class Initiative, and Diversity, Inclusion, & Equity Trainings.

Do Race and Ethnicity Define Your Health?

Archana Gopalakrishnan

In a country where pay and gender inequities are the topic of debates, health disparity does not often get the spotlight. But, did you know that in segregated cities, like Baltimore, the average life expectancy gap between Black Americans and white Americans is twenty years? It’s time we address this and acknowledge that race-based health inequity exists and challenge the opinion: “Being black is bad for your health”.

To keep ourselves fit, we exercise, eat healthy, and keep up with regular doctor visits. What is beyond our control is our genetic make-up and our skin color. Racial disparities contribute not only to the misdiagnosis of several medical conditions, but also increases the risk factor. Paula Braveman, a leading researcher who studies how race affects health, believes that a Black American will live three fewer years than a white person from the same socioeconomic background. Racial inequity is so wide that it affects health care from children to adults and raises the question: “Is being a person of color hazardous for your health?”

It is of common belief that racial health disparities run deeper than the skin color; it is embedded in the genetic makeup. Approximately 8 percent of Black Americans develop sickle cell anemia, a severe form of chronic anemia. Origin of the sickle cell gene in a tropical environment conferred protection against malaria. The Duffy-Antigen Chemokine Receptor (DARC) binds to cytokines released systemically during inflammation. It is also known to bind to Plasmodium vivax, the parasite that is the most common cause of malaria. Nearly 70 percent of the African population, including the Black Americans of African descent, are known to carry the Duffy null phenotype, which renders this race genetically resistant to malarial infection. However, the same DARC mutation is also commonly known as the sickle cell trait, thus increasing the susceptibility to sickle cell anemia. Incidentally, Black Americans with this mutation are also 40 percent more likely to get infected with HIV-1. Thus, a race-specific genetic adaption was successful in preventing one disease but conferred increased susceptibility to another.

As of 2017, Black Americans were 20 percent more likely to succumb to cardiac disease compared to their white counterparts. Hypertension, obesity and diabetes are the three major contributing factors leading to heart failure, all of which are increased in the Black American population. A genetic polymorphism in Apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) gene that evolutionarily developed in individuals of African descent to reduce the risk of infection from Trypanosoma species (causative agent of African Sleeping Sickness) also contributed to renal failure and has been shown to be associated with high blood pressure. However, experts concur that genetics alone is insufficient to explain the alarming increase in cases of cardiovascular diseases among Black Americans. An increase in intake of added sugars has led to a high incidence of type 2 diabetes and obesity, incidence of which are 10 percent higher in Black Americans compared to white Americans. Of noteworthy, in the early twentieth century, diabetes was more common in the white American population as sugar was an expensive commodity and was more commonly used in the affluent community. As sugar became a more affordable commodity, its introduction into various food items, in the form of high fructose corn syrup, also increased. Lack of awareness of the consequences of high sugar intake, and poverty are the major environmental factors that have led to an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, obesity and in turn, cardiac disease.

Genetic polymorphisms that render a population more susceptible to a disorder are known to be influenced by race and ethnicity. Individuals of African descent are reported to be more prone to aggressive periodontitis (AgP). Black American teens were 15-25 percent more susceptible to AgP than white teens. Studies have examined the putative role of genetic susceptibility of individuals of African descent to increased incidence of AgP. Single nucleotide polymorphism in common ion channels seen in individuals of African descent are associated with Ventricular arrhythmia and Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD). Combined with what was being used as SARS CoV-2 treatment options (such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine), this causes 1 in 13 Black Americans to be at a greater risk for SCD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

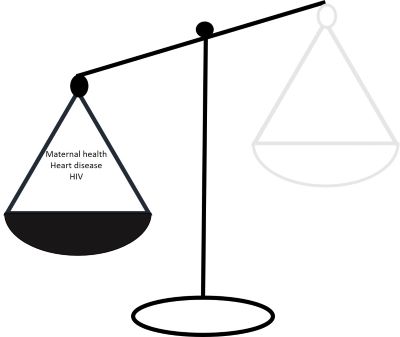

Black American women are 243 percent more likely to have complications from pregnancy compared to White Americans. However, inherited genetic factors do not completely explain this. Up to 15 percent of Black American women of reproductive age in the United States do not have health insurance and/or access to maternal health care. Access to reproductive health that involves counselling and contraceptive health is extremely limited for Black American women. Many hospitals that serve Black American women have very low-quality maternal care. Most of these factors, however, do not explain why Shalon Irving, a CDC epidemiologist, with a dual doctorate in Sociology and Gerontology died just a few weeks after giving birth to a baby girl in January 2017 or why affluent people like Beyoncé and Serena Williams suffered severe complications during delivery. Lack of awareness and poverty are not the only factors that determine the plight of pregnant Black American women. CDC reports that Black American women over the age of thirty are four to five times more likely to die due to pregnancy related complications such as cardiomyopathy, hypertension (pre-eclampsia) and pulmonary embolism (as was the case with Serena Williams) than their white counterparts. Dr. Allison Bryant Mantha, Vice Chair of quality, equity, and safety in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston explains that implicit bias and structural racism affect women’s healthcare. Often, signs and symptoms of Black American patients are missed or left undiagnosed. Despite being acutely aware of signs of complications in her body, Serena Williams’ concerns were initially disregarded, delaying a potentially fatal diagnosis. However, a large majority of Black American women do not get their concerns addressed in time and thus end up becoming a statistic.

While the emergence of the DARC null phenotype renders the Black Americans more susceptible to HIV-1 infection, paradoxically, it also prolongs their survival. Yet, in 2017, Black Americans contributed to 43 percent of the AIDS mortality rate. Besides, high HIV prevalence does not alone explain the very high rate of HIV-1 positive cases within this race, an infection that is primarily acquired only if bodily fluids from an infected person enters the bloodstream of an uninfected person. Despite representing only 13 percent of the US population, they account for 42 percent of HIV-1 positive cases. One in seven Black Americans are not aware they have HIV. Lack of awareness and inability to access quality health care contribute to this knowledge gap. Black American women also have a very high rate of STDs, a direct result of limited reproductive healthcare access.. These factors combined with fear and stigma has marginalized the Black Americans from seeking medical care.

Genetic predisposition, poor lifestyle, and poverty together could explain to an extent the health disparity in Black Americans today. However, Dr. Arline Geronimus, a public health researcher at the University of Michigan, argues that constant stress can affect the physical health. She coined the term “weathering”, to highlight the erosion of the physical body due to small and big stressors in marginalized people. The weathering hypothesis posits that Black Americans, due to repeated challenges in socioeconomic settings and political marginalization, experience early health deterioration. Her observations were based on the premature decline in Black American women’s health. Structural and interpersonal discrimination, personal danger, material hardships contribute to chronic stress in Black American lives. Weathering also has a profound impact on depression and premature aging in Black Americans. Racial discrimination, oppression, and marginalization have contributed to mental anguish and stress that every Black American, regardless of their socio-economic status is forced to live with.

Race based health disparities do exist. There is no denying this. Community members, medical teams, hospitals and caregivers need to recognize this without prejudice. When a pregnant Black American woman walks into a hospital or clinic, it is important to bear in mind that despite her age and status of social privilege, she is likely to have complications during this time. While increasing awareness and knowledge is important, it is also essential to empower Black Americans and as a community work towards reducing the effects of weathering.

Tackle Inequality in America by Teaching Racially Diverse Signs and Symptoms of Disease

Rebecca Walker

Last month we celebrated Juneteenth, a day remembering when those enslaved in Texas received news of their emancipation. A day which marked a turning point in American history. It is possible that America is now at another turning point. The recent death of George Floyd and following protests should stir up our thinking to ask questions; “In what way am I promoting inequality?” “What are my own unconscious biases?” “Which organizations that I am involved in need structural overhauls?” “How can I use my influence for good?” We have the choice to highlight injustice or to sweep it under the rug. We have to choose to be better.

One and a half centuries after the first Juneteenth celebration, the Black community still has the odds stacked against them, particularly in terms of health. According to the US Census Bureau, when comparing Black Americans to white Americans in 2019, Black populations have consistently higher rates of poverty, unemployment, no health insurance, and lower education status. Indeed, the death rate of Black Americans is higher than white Americans in 39 out of 50 states (rate per 100 000 population). These factors are each massive contributors to the poorer health of many Black American populations.

One contributor to increased death rate that could be easily resolved is delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, many medical schools do not teach students to recognize symptoms of disease in skin of color. Medical students are taught to recognise symptoms of a disease on white skin and therefore often fail to recognise conditions on dark skin. This can lead to a low rate of diagnosis which in some cases could lead to deadly results. For instance, despite melanoma skin cancer being more common in the white population, melanoma diagnosed in Black Americans tends to be more advanced and have a worse prognosis. It is likely that melanoma is missed because many medical professionals are not prepared to diagnose cancer of Black skin.

Moreover, racial inequality is embedded in teaching resources such as textbook and medical curriculum. A recent survey of images in commonly used medical textbooks reported that only 4.5 percent of images represented symptoms in dark skin. However, diseases like meningitis, psoriasis, and Kawasaki disease, an acute inflammatory disease of the blood vessels, present very differently depending on skin tone. Medical students should thus be taught appropriate methods of diagnosis on a variety of skin types. We ought to call for medical schools to use more inclusive textbooks, teach symptom identification in a diverse array of skin colours, and to have diverse representations in practical training sessions. We can sign petitions that challenge medical school curriculums to include diverse skin tone representations.

For those of us that are not clinicians, how can we tackle these issues from the bench? In our research we must address our misconceptions and consider our biases. (Read this shocking article describing how the belief that differences in pain sensation between Black and white patients led to underdosing pain medication.) We should consider how the outcomes of our studies provide solutions that are accessible to all. We should consider whether participants in our clinical trials and clinical research projects reflect the population of Baltimore. We should consider how to recruit a more representative cohort, if not.

Even if our research does not seem to relate to these topics, we can challenge ourselves to be more aware of the effects our research has on Black Americans. Why not read books like “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” to get an understanding of how our commonly used HeLa cells are a product of exploitation of Black American families, then thank Henrietta each time you use those cells (after all, her family still lives in Baltimore). We need to change our way of thinking.

In Conversation with...

Sridevi Ranganathan

During discussions within The UMB Post[doc] editorial team, and amongst our colleagues, we found that many of us would like to have conversations about racial inequity in science and society. However, there is also a hesitancy to have these tough conversations.

Is it ok to ask this? Will I offend my colleague by bringing this up?

Will this question sound like I am putting the burden of ‘fixing the problem’ on the Black American community?

How should I phrase this question?

How do I show that I care and support without overwhelming my friend?

We reached out to two members of the University of Maryland Baltimore community to share their thoughts and experiences about how to have conversations about race in academia. In this section, Dr. Tonya Webb, Associate Professor, University of Maryland School Of Medicine, and Adrienne Kambouris, an MD/PhD student in the Molecular Microbiology and Immunology Program at the School Of Medicine, generously share their personal and professional journey with us, along with insights on how to initiate and navigate conversations about race.

In conversation with Dr. Tonya J. Webb, Associate Professor, UMB

Q: You did your BS at Prairie View A&M University and your PhD and postdoc at Indiana University, followed by another postdoc at Johns Hopkins. Now you are an Associate Professor at UMB. Could you please tell us a little bit about your academic interests and what brought you to UMB?

TJW: My main research interest is in immunology. It fascinates me… the way that our body distinguishes between self and non-self is a learned behavior with an intriguing system of checks and balances. I plan to spend my career investigating the mechanisms used by viruses and tumors to evade and suppress the immune system in order to gain a better understanding of basic immunology and to aid in the development of novel therapies. The research environment is what brought me to UMB. It is intellectually stimulating, supportive, and collegial, as well as resource rich.

Q: What in your opinion is the primary reason for racial inequity in academia?

TJW: Ignorance, there are patterns of behavior that illuminate this pervasive ignorance that can be found in every field, including academia. For example, one can be ignorant and culturally unaware and perpetuate racial inequality, one can witness racial inequality and be ignorant of how to deal with the situation, and current protocols are not in place to adequately address inequity issues or microagresssions with appropriate consequences to enhance competency, rather than complacency.

Q: In your personal and professional journey, did you have any mentors who are/were impactful in your life or career?

TJW: Yes, I have had a wonderful support system throughout my training and the development of my career. From my high school AP English teacher, to mentors in undergrad, my PhD advisor and postdoc mentors, as well as my close colleagues, mentoring committee and departmental chair at UMB have all played a large role in my success.

Q: How have your experiences changed (if they have) as you have progressed in your career?

TJW: I have matured throughout the course of my career and this has changed my perspective and influenced my response to different experiences.

Q: Have you had students or peers approach you about race-based issues? If yes, how did you address the issue? What resources have you pointed them to? Do you feel you had sufficient resources to address the issue? What would have helped?

TJW: Yes, I have had students and peers reach out to me. I have had to rely on my experiences to provide advice. Race equity and social reform is not my area of expertise, but I feel that I have a responsibility to be cognizant of my student’s feelings and concerns and provide all of the support that I can. While I am aware of some resources, it would have been helpful to have list of local resources and facilities as well as additional training in this area.

Q: How can we as scientists and researchers have open conversations about racial disparities?

TJW: By keeping the dialogue open and honest. One should be able to speak without fear of being judged or criticized about their experiences, opinions, and knowledge or lack thereof regarding racial disparities.

Q: Do you think it would be helpful if individual departments in every school would have a more open discussion with students and faculty about addressing the issue of diversity and inclusion? How would you envision these discussions happening?

TJW: Yes, I think that even at the departmental level having an open forum may be too large. It would be good to have students to have a monthly discussion where they can discuss their experiences and may be have a couple of faculty/ staff to act as moderators. I think that workshops on cultural sensitivity, race equity, and best leadership practices with time for open discussions would be helpful for faculty.

Q: What role do you think students and early career scientists like postdocs can play in effecting a positive change given that they do not have any administrative powers?

TJW: Early career scientists are role models and can be a positive force for change. One does not need to have administrative powers or be in a top leadership position to advocate for change and to engage others in ways to bring about changes to make the institution fair for all.

Q: Being a successful research scientist and a woman of color- what inspiring story/advise do you have for students and postdocs from diverse ethnicity?

TJW: My advice for trainees is to always believe in yourself—trust in your talent, intelligence, and abilities. Remember that as a person from an underrepresented group, you have had to work twice as hard and have faced numerous challenges, so you have earned your position. Also, place yourself in the best position to be able to take advantage of opportunities (be prepared) and have fun!

Q: Given the current climate, what are you going to be mindful of as you make advances in your professional life?

TJW: I am going to keep in mind the sacrifices that others made so that I can do what I love. My goals are to be respectful, listen, and to take action to help increase access and opportunities for others.

In conversation with Adrienne Kambouris, MD/PhD candidate, UMSOM

Q: Could you please tell us a little bit about your personal and academic journey? What do you work on now?

AK: I was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland, but after high school I joined the US Army and served for over ten years. In time, I deployed to Iraq for a total of twenty-seven months. I also married my husband, Steven, and we now have three children.

I joined the Army in order to afford college. In 2016, I graduated from Augusta University with a BS in Cell and Molecular Biology and Chemistry. I am currently in my fifth year of an MD/PhD program, studying Chlamydia pathogenesis in the Molecular Microbiology and Immunology Program.

Q: What in your opinion is the primary reason for racial inequity in academia?

AK: I believe the primary reason for racial inequality in academia is a lack of representation. I didn’t meet a Black person with a PhD until I started my graduate education at Maryland. If we aren’t exposed to people who look like us in spaces that are foreign, we think that we don’t belong. We can’t be what we can’t see.

Q: In your personal and professional journey, did you have any mentors that are/were impactful in your life or career?

AK: I had too many to name while I was in the military. Every step of the way I sought the mentorship of others. In undergrad, the entirety of the faculty in the Science Hall were supportive of students and wanted the best from them. But particularly, Dr. Jessica Reichmuth, Dr. Amy Abdulovic-Cui, and Dr. Christopher Bates developed my love of science and encouraged my curiosity. They gave me the opportunity to take part in their long term, multi-faceted research project, and once I proved proficient, let me work with autonomy. In that time, I gained confidence in my abilities as a scientist and wanted to pursue it in my future. Dr. Reichmuth encouraged me to apply as an MD/PhD student.

Q: Given the recent incidents and the spotlight on racial inequities, have your fellow students and colleagues reached out to you to check in? Have these interactions been mostly positive or negative for you?

AK: I called it “National Check on Your Black Friend Week.” They were being thoughtful, but it became mentally and emotionally exhausting to respond. I don’t mind having difficult conversations, but it was a constant stream of conversations. It was overwhelming.

Q: How can we as scientists/researchers/physicians have open conversations about racial disparities?

AK: We’re all knowledge-seeking factfinders. We’re driven by data. We know that the disparities exist. We also naturally want to find answers. The way to have these discussions is to have them.

Q: Do you think it would be helpful if individual departments in every school would have a more open discussion with students and faculty about addressing the issue of diversity and inclusion? How would you envision these discussions happening?

AK: I think the effort should be more devoted to recruitment and creating an environment for diverse students and faculty to thrive. We owe it to ourselves to have a diverse community on campus, and that includes diversity of thought. Underrepresented minorities bring life experience and knowledge that others cannot. When we create an environment where we all feel valued, ideas can be discussed openly and science can advance.

Q: What role do you think students and early career scientists like postdocs can play in effecting a positive change given that they do not have any administrative powers?

AK: I’m currently experiencing this: while they do not have administrative powers, they are able to mentor. I’m incredibly grateful for the post docs that take the time to help me develop as a scientist, namely Dr. Alison Scott. They are also able to advocate for and help recruit more diverse faculty and students.

Q: Being a successful research scientist, an Army veteran, a wife, a mom, and a woman of color- what story/advice do you have for students and postdocs from diverse ethnicity?

AK: I’m a Tillman Scholar and at one of our annual summits we discussed imposter syndrome and how to exist in professional spaces. From that discussion, I will always remember this quote: “I belong where my feet are.” We are not a homogeneous, interchangeable race of people. We are individuals with different interests, skills, and desires. That can lead us to any discipline, any field, any institution. And where ever we end up, we belong there.

Q: Given the current climate, what are you going to be mindful of as you make advances in your professional life?

AK: I have been considering what questions to ask programs as I am interviewing for residency. I want to know how institutions will expect me to respond in potentially racist situations (such as requesting a different doctor) and how attendings would support me in those instances. I always consider the diversity of a program, not only if URMs are present but how frequently they are selected into a program. And if there aren’t URMs at a program, I would be concerned as to why. I am constantly looking for opportunities to mentor students through this process, so as I progress through my career I will continue to reach back and help others on their path.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Dr. Natalie D. Eddington, Dean, UMB School of Pharmacy

Sridevi Ranganathan

Dr. Natalie D. Eddington earned her BS at Howard University and her PhD from the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. She started her career as an Assistant Clinical Director at Pfizer Inc., where she worked on Phase I and Phase II drug development processes. She returned to UMB School of Pharmacy as Assistant Professor in 1991. She became chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences in 2003 and was appointed as the Dean of School of Pharmacy in 2007.

We talked to Dr. Eddington about her professional journey and her insights on diversity and equity in academia.

Q: Starting out as faculty and now being the Dean of the UMB School of Pharmacy, how have your experiences changed as you have progressed in your career?

When I was an assistant professor new to the university, I had such an inwardly focused perspective. I was all about starting up the lab, getting grad students, writing grants and papers. I didn't have a great understanding of the department or the university. But as you grow in the work that you're doing and your level of confidence, you sort of look up and see how things could be better. Then you start wanting to change, wanting to implement things, getting to know your ecosystem, your faculty and staff. And so that led to being a department chair. I think the same thing went forward to considering being a dean. It's sort of like- I see things and I think I have the expertise to support, I bring value, I have a perspective. As a dean, you've got to do the right thing for your colleagues as best as you can. You want them to thrive. You want them to achieve their potential. Having the opportunity to provide the resources, the facilities, and an educational platform that they need to do that-that is your role. I think that those things were important at every step of my journey in higher education.

Q: What in your opinion is the primary reason for racial inequity in academia? Do you think the inequity is due to recruitment issues, or the lack of dedicated funding to support diversity programs, or are there fewer candidates applying for these positions?

I think it is all of the above. In order to diversify academia, it has to be a priority. There are significantly higher number of candidates of color. Despite an increase in the number of schools of pharmacy over ten years, the diversity has not changed. That data was very sobering. I think, there was not an emphasis on that (diversity) during this growth.

When I look at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, it's not as diverse as I would like it to be. It is challenging on many fronts. You have a diverse faculty, and everyone is looking to bring them to their university or their school. So that's a challenge. Working on developing and encouraging graduates of color to consider academia, is also a challenge.

Q: One thought is that race-based disparities and inequities start at the primary education level, and the disparities are compounded at the university level. If the problem starts in early education, what can higher education institutions like colleges and universities do to correct the course? Can they sponsor funding programs or partner with early education institutions?

I think that's a great idea. But if we're going to enhance diversity in middle school and high school, we have to be diverse. We have to look like a diverse community in order to let everyone know this is normal. This is how we look as a community. And I think that's sometimes difficult. I think the university is committed to building diversity, so I think we will get there and we will look back at some of these times and really understand how much we've enriched our community, our university, by the diversity that we have.

Q: In the commentary about your article, Dr. Hrabowski of UMBC talked about the need for mentorship to promote diversity in academia. In your personal and professional journey, did you have any mentors that are/were impactful in your life or career?

I did my undergrad pharmacy degree at Howard University. It is a historically black college. There were two Black male faculty members who were mentors to me. It is always important for students to have mentors that see what they are capable of, because most times we don't know what we're capable of. It's all about the confidence. When others that you respect tell you those things, they matter. And I think that is another thing that is very important in higher education and in schools and colleges like ours. There has to be someone there that can understand the perspective of diverse faculty members and understand some of the challenges that they have.

Q: Given the recent incidents and the spotlight on racial inequities, how have you reached out to your students and colleagues?

I think that two things have blended together. One of the things that we did back in February surrounding Covid-19 was that we set up an administrative board that meets every week. One of the things that I was very interested in was the response of faculty, staff, and students. How was this impacting them? We put together surveys every week. We initially saw anxiety, challenges, concerns, and fear. We kept doing that for about five or six weeks. Then we saw some of those things slow down. As it relates to the diversity issues, we've also sent out another survey because we want to be responsive to what's going on and know what people’s concerns are?

We are having conversations about bringing in an Associate Dean-level person for diversity, inclusion, and equity. That would be a way to bring a broader light on the focus that we want to have going forward. I do not want to do things quickly. I want to be thoughtful, listen, and make sure that if we bring someone in, we have a plan and they have a plan. I think that's critical.

Q: Do you think it would be helpful if individual departments in every school could have a more open discussion with students and faculty about addressing the issue of diversity and inclusion? How would you envision these discussions happening?

I think it is important to understand what is important to your community. How you get that information is most likely specific to each school but allowing for a platform to collect that is important. The end goal is to understand what the challenges are and be open to hearing the suggestions.

Q: How can we as scientists and researchers have open conversations about racial disparities? What role do you think students and early career scientists like postdocs can play in effecting a positive change given that they do not have any administrative powers?

I think their contributions are vital. I think that the community that you have in a school or department is there not only to meet the goals and the aspirations of the department and school, but also to provide insights, perspectives, and help to the department so that the school can continue to thrive and to be responsive to the community. That is critical.

I do think that hearing those voices and creating a forum is difficult in higher education, where everyone feels that they have a voice. That is the challenge. I'm willing to listen to anyone. I think that everyone brings value to some extent. And I think in times like this, you know, I hearken back to the point that I made about the surveys, that we implemented earlier this year. I read each one of those surveys and I spent a particularly significant amount of time listening to the comments. I think there is learning in those comments. They are appreciated. And I think that people just don't need to be shy, at least with me.

Q: Given the current climate, what are you going to be mindful of as you make advances in your professional life?

The reason I spent time pulling together ten years of data that inform these manuscripts is to look at diversity and making sure of doing a better job with truly implementing diversity. At the School of Pharmacy, we don't have a diversity officer and Associate Dean yet. Some schools do. That is something I am focusing on. I want to have conversations with the faculty to see where they are. I think that's important to really look at diversity, as we have a health focus at the School of Pharmacy. We know that there are disparities in access to care. So, all of those things fit well in our academic programs and in reminding us of the diverse community that we live in. We have to be mindful of what that means and what that calls us to do.

Q: Being a successful research scientist and a woman of color- what story/advice do you have for students and postdocs from diverse ethnicity?

I think that you need to speak up when you feel that things are not appropriate. You need to realize that we all might look different but are basically all the same. Your perceptions of who you are minimize what you can be. You really need to think of yourself as being capable of doing anything that you want to do. I think it's important to not limit yourself in what you want to do. Our limitations are sometimes our environment, but sometimes we are the ones that limit ourselves. So, we have to learn not to do that and we need to be aspirational. It takes a level of believing in ourselves and maybe sometimes some of us are overconfident, but that's better than not being confident any day.

Racial Disparity in Grant Funding and What We Can Do

Long Jiang

Marches against racial discrimination broke out across the United States after a Minneapolis police officer pinned George Floyd to the ground by his neck and caused his death last month. The consequences of this brutal and blatant event have since been felt in every professional domain. This event caused scientists around the world to focus their attention on institutional and systemic racism against African Americans in academia.1

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) strives to enhance diversity, innovation, and discovery in science. However, racial disparity in grant funding persists. A few years ago, several studies that focused on NIH R01 applications found that, compared with White applicants, African American applicants had a lower successful funding rate, even after controlling for factors such as the applicant’s country of origin, training, and educational background. 2,3 In a follow up study, published in Science Advances in 2019, the authors used data from nearly 160,000 applications submitted between 2011 to 2015.4 The authors found that African American scientists have lower submission rates, impact scores, and average discussion rates in receiving R01 funding compared to White scientists. This study made an interesting observation in that Black applicants are likely to submit applications on topics that usually have lower funding rates. Grant applications that included words such as socioeconomic, disparity, psychosocial, adolescent, risk, health care, and lifestyle were less likely to be funded (success rate 11.2-17.2 percent), whereas applications containing words such as cartilage, skin, osteoarthritis, corneal, neuron, prion, and iron had a higher chance of getting funded (success rate 12.5- 28.7 percent) In addition, a great number of Black scientists mainly focused on disease prevention and intervention.

In June 2020, Erosheva et al analyzed NIH R01 applications from 2014 to 2016, and found a 45 percent funding gap between Black and white applicants.5 Even after controlling for key application and applicant characteristics, such as career stage and area of science, the authors found that Black scientists receive worse scores on Investigator(s), Environment, Significance, Approach, and Innovation categories.5,6 The authors of the study stress that understanding why Black primary investigators are not considered to be outstanding in these dimensions of assessment is the next step for deeply understanding Black-white disparities in the early phase of the R01 review process. They also stress that their data only show associations, rather than drawing causal conclusions. The authors suggest that further investigation might focus on choice of study topic, differences in mentoring experiences, cumulative effect of disparities over a researcher's career, and co-author networks.5,6

NIH remains committed to focusing on this gap and understanding what can be done to shrink it. In a recent NIH Scientific Workforce Diversity Actions and Progress: 2014-2019 report, the gap between RO1 funding rate of African American versus White investigators persists but was slightly narrowed from 2000-2006 (17.1 percent AA/B and 29.3 percent white) to 2013 to 2018 (11.3 percent AA/B vs. 18.1 percent Wqite). In addition, over these five years, there has been a substantial increase in the total number of R01 applications and awards to African American applicants.7

What else can we do? It is a difficult question. Some people think it is time to reform the NIH grants evaluation system by making it a blinded process. Alternatively, John Ioannidis from Stanford University proposed a system similar to the MacArthur Foundation, which funds promising individuals rather than specific proposals.8 A funding system should be transparent and fair and provide equal opportunities to African American scientists. Universities and institutions could also play a helpful role and launch programs to support and train early career African American scientists, such as helping them avoid topics that have lower funding rates, helping them publish high-quality articles, helping them extend their network, and so on. The NIH, universities, and individual scientists need to work together to solve this issue.

References:

1. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2245743-scientists-around-the-world-are-striking-against-racism-in-academia/

2. D. K. Ginther, W. T. Schaffer, J. Schnell, B. Masimore, F. Liu, L. L. Haak, R. Kington. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science 333, 1015–1019 (2011).

3. D. K. Ginther, J. Basner, U. Jensen, J. Schnell, R. Kington, W. T. Schaffer. Publications as predictors of racial and ethnic differences in NIH research awards. PLOS ONE 13, e0205929 (2018).

4. T. A. Hoppe, A. Litovitz, K. A. Willis, et al. Topic Choice Contributes to the Lower Rate of NIH Awards to African-American/black Scientists. Sci Adv. 5(10):eaaw7238 (2019).

5. E. A. Erosheva, S. Grant, M. C. Chen, M. D. Lindner, R. K. Nakamura, C. J. Lee. NIH peer review: criterion scores completely account for racial disparities in overall impact scores. Science Advance; 6(23):eaaz4868 (2020)

6. https://phys.org/news/2020-06-racial-disparities-peer-scores-nih.html.

7. https://diversity.nih.gov/sites/coswd/files/images/docs/ACD_2019_June_13_Valantine_Wilson_FINAL.pdf

8. J. P. A. Ioannidis. More time for research: fund people not projects. Nature, 477(7366):529-31 (2011).

July Events

Careers in Science: Panel for Academic Administration - July 14th 12-1 PM (Register Here)

Careers in Science: Panel for Academic Faculty - July 21st 12-1 PM (Register Here)

Scientific Research Paper Writing Class Wednesdays 12-1PM*

How To Manage Conflict - July 28th 12-1 PM (Register Here)

*Please check your inbox for emails with more information and registration links for these events

Postdoc Achievements

Pavlos Anastasiadis

Erin Reinl

Dr. Erin Reinl earned her PhD in Molecular Cell Biology in 2016 from Washington University in St. Louis in the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. During her graduate work she identified a novel sodium leak current that regulates uterine contractility and promotes successful parturition. Being in the Ob/Gyn department in graduate school, she gained a greater appreciation for the profound importance and complexity of the maternal-fetal relationship in healthy human development. Thus, in her postdoc she shifted her focus toward studying the contribution of maternal-fetal cross talk in fetal brain development. Mentored by Dr. Margaret McCarthy, a leader in the field of sex differences research, Erin’s work focuses specifically on how the maternal and neonatal immune systems sculpt the development of sex differences in the brain, with an interest in how sex predisposes the occurrence of particular neuropsychiatric disorders. Erin was awarded an F32 through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to study this topic in 2018. In addition to doing research, Erin enjoys working with students. She participated in the Collaborative Teaching Fellowship Program during the spring semester (2019) at Loyola University and with the Baltimore Underground Science Space (BUGSS).

Dr. Sara Keefer

Dr. Sara Keefer received her PhD from Boston College in the Psychology department in 2018. Her dissertation work examined the role of anamygdala-prefrontal neural circuitry involved in appetitiveassociative learning. She is now a second-year postdoctoral fellow at UMSOM in the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology in the laboratory of Dr. Donna Calu. Sara’s main focus is to examine behavioral and neurobiological differences that underlie addiction vulnerability. Only a subset of individuals who try drugs of abuse transition into addiction, and Sara is committed to understanding the neurobiological differences between addiction-prone and addiction-resistant individuals. Dr. Keefer is utilizing complex learning theory applications in combination with sophisticated neuroscience techniques to understand how some individuals change their behavior when necessary, while others cannot – a critical feature of addition-related behavior. Importantly, using chemogenetic, optogenetic, and electrophysiological techniques, she is investigating how several neural circuitries are differentially involved in addiction-prone and addiction-resistant individuals. She has presented at the Amygdala Function Gordon Research Conference and Society for Neuroscience conference. She recently published her research findings in Journal of Neuroscience, Behavioral Neuroscience, and Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. Dr. Keefer’s desire is to begin an independent research career to identify innate differences in the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction vulnerability and motivated behaviors.

Dr. Stuart Weston

Dr. Stuart Weston conducted his PhD research at the University College London, UK, in the Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology under the supervision of Dr. Mark Marsh. His graduate work was focused on developing understanding of the interferon-inducible transmembrane proteins and the role they play in inhibiting viral entry to cells. After he was awarded his Ph.D. in 2016 he moved to Baltimore to join Matthew Frieman’s lab at the School of Medicine. Until the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, his research had been centered around identifying novel host factors involved with replication of coronaviruses and influenza aiming at identifying potential broad-spectrum antiviral drug targets. Ever since the emergence of Covid-19, all research focus has moved to testing approaches to combat SARS-CoV-2. Stuart has been involved in performing screens on FDA approved drug libraries looking for chemicals that could potentially be repurposed for antiviral therapy. Another crucial aspect of his work has been to test vaccine candidates in collaboration with various industrial partners. As Covid-19 is an ongoing global health emergency, Stuart’s work in the Frieman lab will remain critical for years to come. In particular, he enjoys the clinical aspect of SARS-CoV-2 with research that could have direct translational applications in the clinic. After his postdoctoral training, Stuart plans to transition into an independent position to continue his work on studying human viruses with the potential for pandemic spread (e.g., coronaviruses and influenza). Improving our understanding of the biology of such viruses and looking for potential broad-spectrum antiviral drug targets to allow us to be better equip for outbreaks in the future, will remain a critical component of Stuart’s work.

Dr. Cheryl Armstrong

Dr. Cheryl Armstrong earned her PhD in the Molecular Medicine program at UMSOM, where she also studied cancer biology. Her thesis research was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Jeffrey A. Winkles and was focused on the regulation and function of the cytokine TWEAK and its cognate receptor Fn14 in solid tumors. She joined the laboratory of Dr. Silvia Montaner as a postdoctoral fellow, where she is currently in her third training year. Her work focuses on the role of ANGPTL4 in pathological angiogenesis, which contributes to multiple diseases (e.g., Kaposi's sarcoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, diabetic retinopathy, and corneal neovascularization). Dr. Armstronghas also been working as a part-time intern for Biocentury, a biotech-focused business journal. She is interested in a career as a scientific writer. As arecipient of a T32 training grant in Cancer Biology, she has been working on a collaborative study with Dr. Abraham Schneider. Her T32 work is focused on how ANGPTL4 may promote lymphangiogenesis and subsequent metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma.

If you would like to submit a postdoc we can highlight or a specific achievement from a postdoc, please fill out this form.

Nerdy Humor

Credit: Mohd Shameel Iqbal, Postdoctoral Fellow at University of Maryland, IHV, Baltimore