The UMB Post[doc]

August 2020

Current Status of COVID-19 Vaccines

The Sword of Damocles Over International Postdoctoral Scholars

August Career Development Events

Global Perspectives Conversation Program

Introduction

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the third issue of The UMB Post [doc].

Scientific innovation thrives on the freedom to collaborate freely and exchange ideas and resources. Students, researchers, administrators, and experts, regardless of their nationality, come together to solve a problem. Such team effort benefits the entire world and makes science and education inherently international and diverse. Recently, some visa restrictions were imposed (and then partly reverted) that affected international students, researchers, and workers from continuing their education or employment in the United States.

In this issue, we want to highlight the contribution of international researchers and scientists to the academic and research life at UMB and science.

Enjoy reading!!

The UMB Post[doc]

Global Connections Within UMB

Archana Gopalakrishnan

Nearly a decade ago, when I landed in the United States, I dragged my groggy-eyed, jet-lagged self to check-in at the International Office of my institution. As an international student, this was also my first stop to make connections and learn more about what it means to be an international student in the United States. The University of Maryland Office of International Services (OIS) sits on the third floor of the Campus Center. It is composed of a small but dedicated group of people who ensure the legal stay of over 800 international students and scholars employed at UMB. The primary role of any OIS is to serve as a liaison between the international scholar and the US government. They help file your visa, maintain your legal status, and offer guidance while crossing international borders. However, OIS at UMB goes one step beyond to ensure that international students, scholars, and employees can blend into Baltimore's vibrant social and cultural life. They are focused on promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the campus and host programs to cater to the same.

UMB has set up the International Student Peer Mentorship program to help incoming international students adjust to a new cultural and social environment. This program matches an international student with a peer mentor who helps the student acclimate and navigate unfamiliar academic and cultural settings. Any senior graduate student, postdoctoral fellow, and junior faculty can serve as a mentor. A recent PhD graduate from the UMB School of Medicine, Manasa Srikanth, participated in this program a few years ago and served as a mentor. "During my time as a PhD student, I have had several new international students reach out to me. I have been able to serve as a peer mentor for them, sharing my experiences with living in Baltimore, labs to select for rotations and areas to look for housing," says Manasa. "As a new international student, you tend to search for others like you, those who understand your language, your social and cultural norms. This [peer mentorship] was something that I missed when I first came to the US in 2013. I would have immensely benefited from an interactive program such as this," comments Manasa.

The Global Perspective Conversation Program (GPCP) is another recent initiative by OIS that aims to facilitate conversations on global issues between UMB students and postdoctoral fellows. GPCP encourages people from diverse backgrounds to engage with one another and appreciate different perspectives on global matters. Such conversations can help broaden one's perspective in a culturally and socially diverse society. I have been honored to serve as a facilitator for this program the past year. This role gave me, an international postdoctoral scholar, the opportunity to meet students and scholars from across the globe, learn about their culture, acknowledge the challenges they encounter in the US academic system, and appreciate the steps they take to blend into their environment. Another international scholar, Mohammed Shabayek, Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of General Dentistry, UMB, participated in GPCP with the hope of understanding the city of Baltimore and its culture. "This program is the only activity I encountered that reduced the feeling of marginalization, and I would recommend more focus on ways to incorporate internationals in cultural activities," notes Mohammed who hails from Egypt. Thiago Bernardino de Almeida, a visiting PhD research fellow who has been at UMB for the past eight months, says, "Coming from Brazil, I wanted to hear and share my experiences with foreigners in the UMB environment. I think that the receptive environment during these meetings enabled me to participate in personal discussions and hear about the different challenges of being a foreigner in the US. I am confident that programs like these would benefit more international students, and I encourage UMB to promote this more." This month’s issue features a special focus article on this program by guest contributors.

The University Student Government Association (USGA) is the campus-wide government that represents all UMB students. The USGA Senate recognizes and supports several student-run organizations in the University that promote diverse social and cultural events, such as the Indian Association, Chinese Students Scholars Association, United Students of African Descent, and the International Students Organization, to name a few. While all these organizations serve as a voice for students of the organization's ethnicity, they also serve as a platform to bring together all UMB students and scholars (international and non-international) to experience diverse social and cultural events and foster interpersonal and interprofessional development.

Are you an international student or scholar who is trying to find an identity within UMB? Or are you non-international UMB personnel who would like to learn more about the global community that makes UMB so rich and diverse? Get involved in these different programs, advertised in The Elm, that bring the UMB community together. Subscribe to the USGA supported organizations' emails and attend their campus-wide events. We can make a difference in enriching the global connections within UMB. So, let's connect!

Current Status of COVID-19 Vaccines

Awadhesh K. Arya

Vaccines are considered the most potent weapons to combat infectious diseases. Vaccines are essentially antigens, consisting of one or a combination of the following components: a complex of pathogen-derived molecules, their synthetic substitutes, inactivated pathogens, and adjuvants (enhancers of the immune response). Vaccines prevent the disease by priming the immune system to mount a protective response against the target pathogen. Unsurprisingly, the incidence of many diseases like smallpox, polio, mumps, measles, rubella, pertussis, and influenza have been reduced dramatically by targeted vaccination. No effective vaccine is currently available for several other infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV. Nonetheless, painstaking efforts to understand the disease pathogenesis mechanisms have enabled us to manage the above three disease with effective combination therapies.

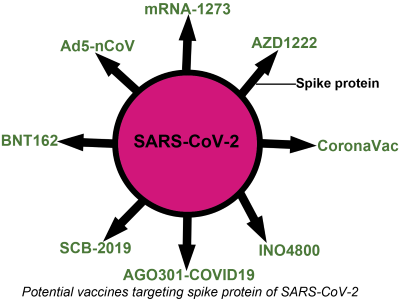

The genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, was published on January 11, 2020. Since then, several research organizations and industries have been working around the clock, utilizing diverse technology platforms including live attenuated vaccines, viral vector-based vaccines, recombinant protein-based vaccines, DNA vaccines, and mRNA vaccines, to develop a vaccine to deal with current COVID-19 pandemic. Worldwide, twenty-seven vaccine candidates are in different stages of clinical trials and more than 140 are in preclinical evaluation. Most COVID-19 vaccine candidates encode the message for full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein or the immunodominant epitope (receptor binding domain – RBD) of the spike. On the other hand, the inactivated virus vaccines (CoronaVac-SinoVac, Covaxin-Bharat Biotech) are comprised of chemically or genetically inactivated viruses that induce antibodies against several viral proteins. Inactivated viruses, though challenging to produce at large scale, have a higher likelihood of success.

To date, five vaccines have entered Phase III clinical trials for large scale efficacy testing of the vaccine. The Ad5-COVID19 vaccine developed by CanSino Biologics has been approved as an especially needed drug for use by the military of the Peoples Republic of China. The Ad5-COVID19 vaccine is a weakened human common cold virus (adenovirus, which infects human cells readily but is incapable of causing disease) to deliver genetic material that codes for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the cells. On administering this form of vaccine, the adenovirus carrying the genetic material encoding SARS-CoV-2 spike protein infects the host (human) cells. This alerts the host immune system which creates antibodies that will recognize that spike protein and fight off the coronavirus. The memory of this vaccine ‘attack’ can help the immune system combat any future viral infection exposures more readily and robustly. Another early front runner is AZD1222, an adenovirus-vectored vaccine developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca, which is a recombinant vaccine generated by cloning SARS-CoV-2 spike in the Chimp Adenovirus. This vaccine is expected to generate a robust immune response potentially providing enhanced protection, as adenoviruses themselves are immunogenic.

Among the most promising vaccine candidates is the messenger RNA (mRNA)-based vaccine developed by Moderna (mRNA-1273) that has begun its human safety and efficacy clinical trials (phase III) in 30,000 individuals. Moderna's mRNA-1273 entered clinical trials just sixty-six days after SARS-CoV-2 was first sequenced, showcasing the potential for nucleotide-based vaccines, especially the advantage of scaling up production under pandemic situations. Like traditional live-virus vaccines, these vaccines deliver a genetic sequence into a host cell and co-opt host machinery to express antigens of interest. However, rather than using a weakened SARS-CoV-2 to transport the code, Moderna's vaccine uses a synthetic lipid nanoparticle to carry the mRNA templates. Like most other COVID-19 vaccines in development, Moderna's candidate attempts to train the immune system to recognize SARS-CoV-2's spike protein, which the virus uses to bind to and enter host cells.

In addition to nucleotide-based and adenovirus-based approaches, Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline, are focusing on a protein subunit approach. Their lead vaccine candidate consists of the spike antigen, combined with an immunogenic adjuvant to trigger a strong immune response. The two companies hope to start clinical trials in the second half of 2020. Some researchers and companies are also attempting to use whole-virus approaches, wherein the immune system is trained to recognize weakened or killed SARS-CoV-2 Historically, this method has proven to be effective in combating diseases such as defeat polio, hepatitis A, and rabies. But these vaccines are challenging to create, and production is time-consuming especially in a pandemic situation when a large supply of vaccines would be needed quickly. In this approach, a virus is often introduced in the allantoic fluid of the fertilized chicken egg and it replicates in the membrane surround the fluid. After about three days, the virus-containing fluid is harvested from each egg and the rest of the manufacturing process proceeds. Millions of hens would be needed to mass-produce a vaccine for worldwide distribution. Also, working with a live virus is inherently risky.

The disruption caused by the ongoing pandemic to our everyday lives may make us feel like the vaccine development process is taking too much time. But it is very important to keep in mind that the current scenario still represents a fundamental step-change from the traditional vaccine development pathway, which takes on average over ten years, or the accelerated five-year timescale for the development of the first Ebola vaccine. In the midst of a pandemic, we have five vaccine candidates in different phases of development. This has been possible because of the extensive knowledge gained over the years via painstaking research and also learning from previous coronavirus outbreaks. Extensive knowledge of vaccine studies during SARS and MERS outbreaks in 2003 and 2012 provides a strong background to better understanding of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Improved computer-based analyses to understand the interaction between antigenic component and immune system response and the utilization of platform technologies, play a major role in quickly creating a vaccine candidate to test. Right now, let’s join the rest of the world in hoping that a safe and effective vaccine will be available under emergency use or similar protocols by the end of 2020 or early 2021.

Moving Forward Together?

Cali Calarco

.jpg)

The University has done an exceptional job at keeping on-campus risk low, and it was recently reported in last week’s Front Line News that there have been no cases of on-campus COVID-19 transmission since reopening began. The School of Medicine’s Dean Reece also said that our scientific community has been using their time away from the bench effectively, citing a 50 percent rise in grant submission rates. While all these positive steps forward are moral boosting, do they tell the whole story?

With new requirements for self-monitoring and self-reporting symptoms, as well as new guidelines for social distancing, reduced room density, and regular disinfecting, postdocs and others conducting wet-lab research have been allowed back on to campus after more than two months of essential access only. Returning to campus has brought a range of emotions: relief to be back, renewed confidence for being able to accomplish concrete and tangible goals, exhaustion from the added vigilance and mask wearing, as well as a general surrealness of finding calendars left on March and notes about upcoming deadlines and meetings now long passed. Alone in the lab, it feels like a perpetual weekend, but it also feels good to get out of the house and to feel like hours of work are yielding results. Perhaps this was the feeling so many were chasing as they made sourdough bread this spring. The joy of regaining time in the lab and seeing coworkers again (from a distance while masked) is coupled with loss for the aspects of science that are still missing as we continue to socially distance: casual conversation, impromptu experimental advice, and in some cases, coworkers that have not been able to return to campus or to start new positions.

While some of us return, many cannot yet make it back to campus: those who are at high risk for COVID-19 infections or who are dealing with health challenges caused by a COVID-19 infection may have chosen to continue to limit their time on campus; those who have had shifting family responsibilities or who are still actively grieving lost loved ones due to the pandemic; those attempting to manage childcare while most day care, summer camps, and children’s activities remain closed. Childcare concerns will only become more complicated as distance learning resumes for the start of the 2020 academic year. Additionally, some international members of the campus community have been stranded away from campus due to travel restrictions, closed borders, and delays or bans in visa issuance or renewal. While valiant lobbying led to the overturning of the disruptions in student visas for currently enrolled students whose schools are using distance learning this fall, restrictions due to COVID have made new international student enrollment more difficult this fall. Currently, for international scientists looking to start new postdoc positions in the US, visas seem to remain on hold until 2021, leaving many waiting without current employment. Many embassies have only recently reopened and are facing five months of backlogged requests.

Further, grant and manuscript submissions have risen with teleworking, but national trends show that these milestones have been disproportionately achieved by men. As demand for childcare and changes in teaching modalities skyrocketed, the number of papers with women as first authors plunged. Real time data of preprint submissions broken down by gender can be seen here. While this trend has been acknowledged, it is unclear what the long term consequences will be especially for those who are already in underrepresented groups, for early career researchers, and for those looking to enter the job market in 2020 or 2021.

This summer has been a time of political upheaval as the country confronts the history of racism, oppression, and inequality in our institutions, and a time where disparities in access to even basic security have been magnified. It is important that, as we move towards the fall, the academy we return to is one better than that which we left in March. This includes continuing to make space for those who are facing practical limitations this year due to the pandemic and fighting for the return and protection of our international colleagues.

In Conversation with...Dr. Irang Kim

Tramy Hoang

This month we are in conversation with Dr. Irang Kim, a postdoctoral fellow at the UMB School of Social Work. Prior to coming to the US to obtain her advanced degrees, she received her Bachelor of Social Work in South Korea and worked with families with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). She continued her work in this field as she obtained her Master’s and PhD in the United States. Her research focuses on supporting underserved families with children with ASD. She recently finished her tenure as a postdoc at UMB and is currently transitioning into her new role as an Assistant Professor at Tulane University. She discusses with us her passion for her research with ASD families and her experiences with the US immigration system.

Research

“I’m doing research [to provide] support for individuals with autism and their families who lives in underserved areas and minority populations.” As part of her research, Dr. Kim recruits minority families and those from underserved areas to take part in her studies. She says this is difficult, especially in African American families, citing distrust as a major reason. Additionally, these families have a lot to worry about and participating in a research study is not priority so they either do not participate or their participation is not consistent. Because of the difficulty reaching these populations, data is limited which is why Dr. Kim’s research is so valuable. “I feel it’s worth it to do it, even though it’s hard to recruit...I want to develop interventions to support African American parents and also those living in poverty.” These interventions include case management support such as parenting programs. This provides both an incentive to the families but also may provide resources that these families would otherwise not have. While there are resources and support available to families with autistic children, they are not as easily accessible to low income, Hispanic, Black, and immigrant families.

Dr. Kim says racial disparity is another challenge facing many of these families,“African American and Latino families are [generally] diagnosed later than whites.” This can lead to the need for more intensive interventions as well as more trouble obtaining services. Dr. Kim cites lack of education and awareness in these families as well as health professionals not listening to these parents’ concerns when they are raised.

While this pandemic has been challenging for almost everyone, Dr. Kim also discussed some unique obstacles for families with autistic children. First, many of the services that these families may have been using are not available and, without these, the parents worry about their children regressing. Additionally, these children have a set schedule and can become very anxious and aggressive when their schedules are disturbed. They are also very sensitive to sounds, sights, and textures so face masks are also difficult for them.

In response to the killing of George Floyd and the following civil unrest, “we did some qualitative studies (interviews) of African American parents and they’re really concerned about their kids.” The frequency of police violence is disproportionately higher for Black men than for white men. Since aggression and difficulty in communication are common in those with autism, it is understandable that these parents are fearful for the well-being of their children should they encounter law enforcement. “So we try to include that component into our parenting program [such as] how they teach their kids or how they talk to law enforcement or police officers... and also the other side, [we] try to educate law enforcement.”

Immigration

Since Dr. Kim is originally from South Korea, we also asked her to share her experiences and perspectives on the US immigration system.

“It’s been ten years since I moved to the United States... I feel like there’s more opportunities here and also, I like the working environment. In Korea, there are hierarchy relationships and no work life balance... I like the environment here, but I really miss my family.”

“My experience with the F1 (student) visa is not that bad” but she says once she graduated, the process became more difficult. Not only was it expensive to apply for the H1B (working) visa but it also takes a long time. “It took a year to be approved and once I submit the paperwork, I can’t really leave the country so it’s [been] almost two years [that] I can’t go back to my country”. And with the borders being closed, she is unsure when she will be able to go home again.

While she is lucky to be able to get visas approved, there has been times where she was worried about her status. For example, earlier this year, President Trump signed an executive order halting the issuance of H1B visas, which is what Dr. Kim has. At this time, Dr. Kim was in the middle of applying for an H1B visa for her new job at Tulane University and was worried this would interfere with her being able to work. Luckily, she submitted her application prior to the order being signed. “I feel like I’m privileged among the immigrants because I am highly educated, I feel I can get my visa approved easier than other people so I’m very thankful about that. A lot of immigrants really contribute to this country... but the system never value[s] what they are doing.”

SPOTLIGHT ON: Dr. Abhay Andar

Archana Gopalakrishnan

Q: What is Potomac Photonics and what is your role here as a Senior Scientist?

At Potomac Photonics Inc., we innovate methods and technologies to streamline alternatives to conventional manufacturing. We focus on the economies of scale while pushing the envelope on quality standards and device fabrication tolerances. We are committed to creating and maintaining a vibrant workforce in the Baltimore area, keeping advanced manufacturing jobs in the USA and developing the next generation of American engineers to make a significant global impact.

As a Senior Scientist, I lead the MicroFab laboratory, which is an integral part of the Process and Production Technology (PPT) team that focuses on research and development of novel micromanufacturing scale-up strategies. We provide clients with expert guidance for developing viable and cost-effective manufacturing solutions for complex micro-scale devices. We support companies as well as academic labs in conducting risk assessments and developing strategies for translating prototypes into high efficacy commercial manufacturing. Overall, my job augments translation of research prototypes into commercial products, with the broader aim to strengthen innovation and micromanufacturing capabilities at Potomac.

Q: Prior to this, you worked at the Center for Advanced Sensor Technology (CAST) at UMBC as an Assistant Research Scientist. How different was this compared to your current job?

I chose CAST UMBC to pursue my interest in an academic career. Like my current position, my role at CAST demanded scientific rigor and creative thinking. In my current position, I play a key role in the choice of projects, based on my expertise, market research, and risk assessments. However, at CAST, projects stemmed from the interests of the lab leadership. My research at CAST focused on novel research-scale bioengineering solutions to support biopharmaceutical research. My role within CAST involved producing state-of the art microfluidic devices to miniaturize large-scale bioprocesses. The scope of the project involved miniaturizing a biomanufacturing facility into a suitcase-sized device. At CAST, I also enjoyed basic engineering research as well as academic teaching and mentoring responsibilities.

Q: How do you balance your current responsibilities while serving as an Adjunct Faculty at UMBC?

Balancing my teaching responsibilities with a full-time job is challenging, but it gets easier with practice. I enjoyed working with trainees during my time at UMBC and it was important for me to continue teaching and mentoring. As an Adjunct Faculty at the Translational Life Science Technology (TLST), Applied Biotechnology Program, I have greater flexibility in choosing courses to teach based on my schedule and interests. The program is committed to increasing diversity within science education, which is a cause important to me as an immigrant. I also enjoy the freedom to chart the syllabus and invite subject-matter experts as guest lecturers for my courses. For this, my connections across academia and industry have proved an invaluable resource, even providing internship opportunities to my students. It is a fine balance that requires careful planning and regular evaluation based on changing priorities and deadlines. The recent switch to virtual classrooms adds a new level of complexity and the classes definitely keep me on my toes. But I really enjoy it and that helps to manage the challenges.

Q: You did your Bachelor's in India, Master's and PhD in the UK, and came to the US for your postdoctoral research. How has travelling around the world influenced your higher education?

Experiences in each of the countries has been vastly different and I am grateful for each one. I grew up in Mumbai, India, a place that’s a special in my heart. My Bachelor's program in Mumbai is where I really developed a love for cell biology. However, I felt my scientific training lacked access to cutting-edge research. To overcome this, I pursued graduate education in the UK. What drew me to the University of Glasgow was the opportunity to work on an independent research project, which fit my goals perfectly. I learned a lot during the one-year Master’s program and stayed on for a research fellowship for an additional year, until I finally joined a PhD program in Biomedical Science and Engineering. I enjoyed working in the lab I chose and made some great friends. At Glasgow, I was exposed to state-of-the-art equipment and an excellent panel of scientists and instructors. This is where I mastered my skills in nano/micro-fabrication technologies and bioengineering at the newly built James Watt Nanofabrication Center. Also, Glasgow was a vibrant city and I loved the student life there. To apply my skills to projects outside my comfort zone and continue my scientific development, I began looking for opportunities outside Glasgow. Finding good opportunities for immigrant scientists is always tough and the fact that the UK was going through a recession added to the challenge. I moved to Baltimore and joined the UMB School of Pharmacy as a postdoctoral trainee to develop a pharmacy-on-a-chip. This was a relatively new concept in microfluidics at the time and I was excited about the opportunity. In the end, I successfully completed my postdoctoral training across interdisciplinary labs.

Looking back through my nomadic life, I have discovered that I am truly a global citizen. I have fond memories of all places I have resided in along my scientific training. These places and its people molded me into the person I am today and will always have a special place in my heart. Having this international experience and exposure to state-of-the-art technologies has given me a unique perspective in conversations with colleagues, peers and now clients and continues to shape my life.

Q: As an international scholar arriving in the US, how did the experience in UMB shape your career and your personality?

I entered the USA as a J1 Research Scholar. As an immigrant scholar, navigating the visa process takes considerable time, expense, and effort. However, USA is one of the best places for cutting-edge research and I knew this was the right step for me. Research experience in the USA or UK allows for robust scientific training and augments any prospect of a successful career for a young immigrant researcher. One of the major challenges of not being an American citizen though was the ineligibility to most research grant applications in the USA. This remains a major bottleneck for most international trainees aspiring to be academic researchers, coupled with visa, cultural, and lifestyle differences. To remain competitive as a researcher in the USA you often need to take the next big step of applying for permanent residence, which is becoming increasingly difficult too. However, the challenges and adversity made me more resourceful and have contributed positively to my overall development as an immigrant scientist.

Q: As faculty, do you encounter international students at UMBC? If so, how has your interaction been with them?

At UMBC, I come across many international students looking for a chance to prove themselves. I often find students trying to juggle classes with part-time jobs. While this is challenging, I find most students are really motivated to perform well. I find that the most successful students, regardless of their nationality, find community with local and international students. This allows them to integrate successfully and, thus, thrive in their chosen courses and career paths. I also find that international students who seek help and advice from student counselors and prioritize mental wellness cope better with navigating all aspects of student life.

Q: What advice do you have for international scholars navigating the US job market planning to extend their scientific career here?

The immigration system in the US is complicated but necessary for anyone planning to stay here for the long-term. Many of my colleagues on J1 and H1 visas have also been affected adversely by recent ICE regulations, demonstrating that immigration is increasingly precarious. Due to the demand and opportunities in micro/nanofabrication technologies and research in the US, I was keen to settle down here. I recommend any international researcher keen on immigrating to USA to do the following:

- Stay on top of immigration news and your visa eligibility criteria.

- Get an early start with preparing your documents. If you are interested in emigrating to USA, consider working towards your desired immigration status as soon as you commence student or postdoc life here.

- Be aware of any restrictions or necessary waivers from your country of origin.

- Actively work towards establishing a good track record of scientific publications.

- Devote time to extracurricular volunteering to bolster your CV and always maintain an updated CV following an acceptable format.

- Actively pursue reviewing journal articles and conference abstracts.

- Cultivate at least 3-4 faculty mentors beyond your thesis advisor/committee.

- Attend interdepartmental talks and seminars to contextualize your scientific and professional interests and develop networks beyond the student community.

- Regularly monitor your citations from independent researchers to ascertain the impact of your research.

- Generally, each case is unique and one should seek professional student and legal support services to determine the best course of action.

In the end if you do good work, contribute and publish regularly, and conduct your research with the highest ethical conduct, no matter where you end up, you will always move forward in a positive direction in your research career.

The Sword of Damocles Over International Postdoctoral Scholars

Pavlos Anastasiadis

In a matter of months, the rampant progression of the pernicious SARS-CoV-2 virus has brought the academic job market to an abrupt halt nearly on the brink of collapse in many parts of the world. The situation is especially dire in the United States and the United Kingdom, where many institutions depend on tuition fees.

In stark contrast to these hiring freezes of junior faculty and postdoctoral scholars, Germany’s Max Planck Society, which has institutes across Europe, as well as in the United States and South Korea, continues to advertise job openings for early-career researchers, including postdocs, and technicians. This is largely due to the Pact for Research and Innovation, a funding plan renewed by the German government in 2019, aimed at keeping budgets at the Max Planck Society and other German research organizations intact for the next decade.

Back in the United States, the continued upsurge of the virus and the recent economic indicators that prognosticate tumultuous times ahead of us have created a perilous situation for postdocs. Add immigration-related challenges to the mix, and suddenly the existence of international postdocs may draw similarities to the twelve Labors of Hercules. Even outside the setting of a global health crisis, postdoctoral fellows stand on tenuous grounds. Their employment often hinges on annual contracts that may be dependent on variable funding sources. During their tenures in the United States and around the world, postdocs have acquainted themselves with uncertainty, often making them feel as if they live and breathe in professional limbo.

Immigration for international scholars was already arduous under previous immigration visa policies. New travel restrictions in the United States and around the world have made international scientists crumble under the strain. Six international postdocs from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, CA, composed an Op-Ed letter published in Nature describing how “renewing a non-immigrant visa is (currently) next to impossible.” More gravely, legal advice is hard to obtain primarily due to the fluidity of the situation. “Applying for a new visa is not an option, so long as embassies and consulates remain closed and travel restrictions continue to apply,” the six scholars lay out in their article. The anxiety many international postdocs – and students – feel due to a shifting ground of immigration rules is understandable. Much of the tension can be attributed to the uncertainty of the situation which has even legal scholars pondering. Who would not agonize over a nebulous situation created by a storm of ever-changing regulations and global travel restrictions imposed by countries across continents during a raging pandemic?

Sudip Parikh, the Chief Executive Officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, recently published an editorial on how “immigrants help make America great.” After the end of WWII, the United States has created an academic model that other nations around the world have envied and continue to admire. Ever since, flocks of aspiring international scholars and students have arrived to earn academic degrees, train in postdoctoral positions, or complete their residencies. Many of them have made substantial contributions to science and technology that have proven beneficial to the United States and the entire world. In fact, according to the National Science Foundation, more than 50 percent of postdoctoral scholars (for the University of Maryland School of Medicine this figure lies at 63 percent as defined by non-US citizens or permanent residents) and 28 percent of science and engineering faculty in the United States are immigrants. Of the Nobel Prizes in chemistry, medicine, and physics awarded to United States nationals since 2000, 38 percent were awarded to naturalized immigrants.

Parikh goes so far in his editorial as to argue that “preventing highly skilled scientists and postdocs from entering the United States directly threatens this enterprise.” If we genuinely desire to beat SARS-CoV-2 and future pandemics, colonize and terraform Mars, develop innovative cures for human disease, build rockets and satellites that will travel to even more distant corners of the universe and tackle climate change, it is emphatically imperative that we marshal awareness toward a perpetual effort to safeguard international postdocs.

At times when the situation nationally and internationally is disrupting every single facet of our lives, silver linings can be easily overlooked. Regina Dugan, in her recent Op-Ed in the Washington Post, offers a positive outlook to the COVID-19 menace, arguing that, while Sputnik set off the Space Age during the Cold War, the SARS-CoV-2 virus could help spark a Health Age. There are many reasons to suggest that Dugan’s prediction might materialize in the short- rather than long-term. The prospect of a post-pandemic academic Renaissance in life and health sciences is one that should make us all very hopeful.

Online Resources

There is a plethora of online resources to aid international postdocs navigate through these dreadful times. The National Postdoctoral Association is an online resource for international postdocs and students alike with a thesaurus of links, and advice. Two guides that might be of interest are the “International Postdoc Survival Guide” and “Guide to Visas”. Nature Careers has started a series of webcasts as part of Nature’s ongoing efforts to help scientists manage their working lives during the coronavirus pandemic and lockdowns. The University of Maryland, Baltimore's of Office of International Services provides support to international students and scholars. The PROMISE Summer Success Institute (SSI) 2020 organizes a summer conference to be hosted from August 20-22, 2020 for all graduate students and postdocs at the University System of Maryland. SSI will provide “professional development, encouragement, motivation, career advice, peer support, and camaraderie, particularly for underrepresented graduate students and postdocs in STEM fields”.

August Events

PDAC Virtual Career Event: Transitioning to Clinical Research from Academia, Elizabeth Shepherd, PhD, Clinical Trial Manager at Medspace, August 13th, 12:00-1:00*

Promise Virtual Summer Success Institute: Thursday, August 20th – Saturday August 22*

Careers in Clinical Laboratory Genetics: Tuesday, August 25th: 12:00-1:00*

*Please check your inbox for emails with more information and registration links for these events

Postdoc Achievements

Long Jiang

Dr. Myeongjin Choi

After Dr. Choi earned a DVM degree, she received her PhD in Molecular Biology in 2015 from Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea, in the Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistant Pathogen Research under the supervision of Dr. Kwan Soo Ko. During her graduate work, she investigated the antibiotic concentrations at which last resort antibiotics (e.g. colistin and tigecycline) induced resistance. Now she is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health in the laboratory of Dr. Alan S. Cross. During her postdoctoral fellowship, she has been collaborating with three teams in molecular biology, vaccine manufacturing, and pre-clinical research to study host-oriented peptides and conjugate vaccines against antibiotic resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These peptides attenuate, but do not ablate, the host cytokine storm following infection. She is evaluating the protective efficacy of a novel quadrivalent Klebsiella/Pseudomonas vaccine. She is a primary researcher under a grant from the United States Air Force which aims to examine the effect on hypobaria and oxygen levels on burn wound infection. These data will give us fundamental information on the effect of oxygen therapy during air evacuation of soldiers who suffer from burn wound infections. In addition, she earned a postdoctoral fellow award from the Department in 2019. Furthermore, she is working as a reviewer for academic journals in veterinary science and microbiology.

Dr. Humberto Cavalcante Joca

Dr. Humberto Cavalcante Joca conducted his PhD research at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Physiology and Pharmacology in 2018. During his graduate work he mainly focused on understanding key components that regulate cardiac and skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling remodeling in diverse diseases. He is now a second-year postdoctoral fellow at The Center for Biomedical Engineering and Technology (BioMET) in the University of Maryland School of Medicine in the laboratory of Dr. W. Jonathan Lederer and Dr. Christopher W. Ward. His research now focuses on cardiac excitation-contraction coupling and mechanotransduction in muscle cells and diverse other cell types. He was also awarded a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (2019-2021). He recently published his research findings in The Journal of Physiology, The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, and Scientific Reports.

Dr. Shiyu Tang

Dr. Shiyu Tang earned her PhD in Toxicology at the University of Maryland Baltimore in 2018. The heart of her graduate work was to investigate the brain alterations associated with developmental alcohol exposure using neuroimaging techniques. She is now a second-year postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Rao Gullapalli in the Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine. Her research is focused on the study of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Patients with mTBI usually return to work or service seven to ten days after injury without noticeable symptoms at the time of injury. However, symptoms of mTBI may appear later and last for months or more resulting in debilitating conditions that ultimately lead to severe loss in quality of life. The objective of her study is to better understand the mechanisms behind long-term outcomes of mTBI and identify early-stage imaging biomarkers for patients who develop unfavorable outcomes. In addition to the study on patients, she is also working on animal models to identify optimal and cost-efficient animal models for mTBI research, specifically for research on blast-induced brain injuries. She recently published her research findings in Developmental Neuroscience, European Journal of Neuroscience, Frontiers in Neuroscience, and Molecular Imaging. Furthermore, she has served on the organizing committee of the Annual Maryland Neuroimaging Retreat since 2016. She aspires to grow in her academic career and to show her dedication to the neuroimaging community.

If you would like to submit a postdoc we can highlight or a specific achievement from a postdoc, please fill out this form.

Can You Handle the Heat?

Rebecca Walker

Chili peppers are native to the Americas and since travelling the world have found their homes in all kinds of dishes. Whether it’s a South Western Chinese hotpot, a Mexican salsa, or an Indian curry, many cultures across the world enjoy a spicy dish. Yet, while most animals are repelled by the burning sensation, we humans appear to be the only species that seeks it out. So what’s the deal? What’s so attractive about chilis?

The heat of a chili pepper is measured by the Scoville heat scale. A Scoville score corresponds with the number of times a chili extract needs to be diluted in water before it loses its heat. Pure capsaicin, the chemical in chili peppers that is responsible for inducing a spicy sensation, scores 16,000,000 Scoville units, whereas jalapeños which only contain a small amount of the spicy compound, only reach 4,500 Scoville units.

Ever wondered why chili spiciness feels hot? The receptor to which capsaicin binds, TRPV1, is a highly sensitive, efficient and selective channel which resides within nociceptive (i.e pain detector) neurons. TRPV1 is so sensitive, we can still sense the spiciness even after 16,000,000 dilutions! TRPV1 is also sensitive to a wide range of physical and chemical stimuli, each affecting a different part of the channel. Since TRPV1 can be activated with different strengths from different kinds of stimuli, such as physical heat or chemical spiciness, it is truly a polymodal sensor for noxious stimuli. The same channel senses physical heat and spiciness, hence the burning sensation we feel when we eat chilis.

The capsaicin receptor TRPV1, is an ion channel which opens in response to capsaicin binding. As with other members of the capsaicinoid family, capsaicin contains a vanillyl group (a “head”), an amide group (a “neck”) and a fatty acid chain (a “tail”). Capsaicin binds head first into a pocket formed by TRPV1’s transmembrane domains, stabilising the open state of the channel. Spicy compounds found in other foods such as ginger and black pepper highly resemble capsaicin. These compounds bear structural resemblance to capsaicin and can bind to TRPV1, yet their differences correlate strongly with their ability to open the channel. The polymodal nature of TRPV1 allows us to distinguish the differences in the way these compounds act on the channel, allowing us to distinguish the subsequent sensations of spiciness.

Since TRPV1 can be activated by a number of noxious stimuli it acts as an important pain sensor. Therefore, TRPV1 has been targeted by pharmaceutical companies wishing to develop effective pain relief. Unfortunately, since TRPV1 is also involved in heat sensation and regulating body temperature, many pharmaceuticals employed as antagonists against the channel cause hyperthermia. These severe side effects render systemic applications of the drug useless. However, recent knowledge gained from structural studies of the channel provide hope. The binding of capsaicin to TRPV1 causes a more subtle movement of the channel than the large conformational changes to the channel caused by physical heat. Therefore, a more specific inhibitor, which acts more like capsaicin than physical heat, may be able to provide pain relief without the severe temperature regulation side effects.

Capsaicin patches or creams are sometimes used to treat chronic pain. TRPV1 channels are overloaded by excess capsaicin applied as a cream or patch on the skin. This causes massive influx of calcium into the cell which eventually leads to activation of proteases and retraction of nerve fibres of the nociceptive neuron. A day or two of burning skin, effectively kills off the pain sensor in an area of the body for a few months, relieving chronic pain.

TRPV1 therefore represents an interesting and polymodal sensor which is adaptable to a number of different stimuli. We have been benefitting from its ability to spice up our food for years and perhaps will be able to benefit from targeting it for pain relief more in the future. For now, why not try to excite your taste buds with a new recipe?!

Vindaloo for t wo

wo

Vindaloo is a spicy Goan curry which is said to have originated when Portuguese merchants brought pork preserved in garlic and wine to Goa. After adding a few spices, the dish we know today was born. This fiery dish has the potential to activate your TRPV1 channels with chilis, ginger and black peppercorns. Can you handle the heat?

A good curry takes time! For best results, marinade overnight and let the curry cook for a nice long time.

Materials

4 dried Kashmiri chili peppers, deseeded (or substitute ¼ Tbsp paprika and ¼ Tbsp cayenne powder)

¼ inch piece cinnamon stick (or ¼ tsp powder)

¼ Tsp cumin seeds

¼ Tsp Coriander

1-1/2 whole cloves

1/8 Tsp whole black peppercorns

1/8 Tsp ground turmeric

1 Tbsp white vinegar

1 pinch salt to taste

1/2 pound boneless pork loin roast, trimmed and cut into 1-inch cubes (you can use other meats like chicken, or even paneer for a veggie curry)

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 onion, finely sliced

3 cloves garlic, minced, or more to taste

½ inch piece fresh ginger, minced

2 tomatoes, diced

½ cup boiling water

½ green chili pepper, deseeded and cut into strips

1 Tbsp white vinegar

Methods

Step 1: Grind the Kashmiri chiles, cinnamon stick, cumin, coriander, clove, peppercorns, and turmeric with a mortar and pestle or electric coffee grinder until the spices have been ground smooth. Mix with 1 tablespoon of white vinegar to create a smooth paste. Season to taste with salt.

Step 2: Mix the pork cubes with the spice-vinegar paste in a bowl until evenly coated. Cover the bowl and marinate in the refrigerator overnight.

Step 3: Heat the vegetable oil in a large pot over medium-high heat. Cook the onions until golden brown, add garlic, and ginger and cook 5 more minutes then add tomatoes and cook until they start to break down. Add the pork and its marinade, and cook, stirring frequently, until the pork cubes have firmed, about 5 minutes. Pour in the water, bring to simmer, then reduce heat, cover, and cook until the pork is tender, about 40 minutes.

Step 4: Stir in the green chili pepper strips and vinegar. Cook uncovered until the green chili peppers have softened and the vindaloo has thickened, about 30 more minutes. Season to taste with salt before serving.

Enjoy over a bed of basmati rice or with naan bread.

Global Perspectives Conversation Program

Guest Contributors James Wright and Mio Kamijo

The Making

The concept of the Global Perspectives Conversation Program emerged from conversations between James Wright, Multilingual Writing Specialist in the UMB Writing Center, and Cameron Busacca, former International Student Coordinator in the UMB International Services Office and now International Student Programming at the University of Maryland, College Park. Their deliberations unpacked some of the ways traditional conversation programs can often take an English as a Second Language (ESL) frame, upholding the unhelpful “native vs. non-native” speaker binary by positioning so-called “native” speaker facilitators as partners with international students in a process that characterizes the latter speakers’ language practices as in need of correction or improvement. Further, such conversation programs tend to be general in content, deliberately ranging across topics related to everyday life—e.g., grocery shopping, daily routines, favorite movies, etc.

Cameron and James recognized that graduate students and post-doctoral fellows’ literacies and lived experiences call for a different kind of conversation and program that avoid deficiency-based approaches to language practices and that encourages meaningful dialogue about academic, political, and social issues and events relevant to participants’ expertise, research, and concerns—and oriented to social justice and antiracist practice. So, the intent of the Global Perspectives Conversation Program was not to assume a politically neutral grounds for conversation but instead to deliberately center culture and identity as ever-changing sites of critical inquiry in which participants share not only their multiple viewpoints and information about their lives and scholarship but commit to transformative talk that engages difference, makes visible injustice, focuses on local Baltimore contexts, and seeks to recognize the complexities and conflicts surrounding the practice of health and human services in our city and beyond.

In 2018, Cameron shifted positions to College Park and Mio Kamijo joined James as co-coordinator of the program. Mio brought her expertise and long experience with international students and programs, language learning, and education, redefining the Global Perspectives Conversation Program’s organization, recruitment, and training. She developed and continues to refine outreach, scheduling, and recruitment mechanisms that have completely transformed and expanded the program’s reach across all UMB schools. She manages the weekly conversation sessions, often joining and participating in them, and, along with James, has revised the annual facilitator training and ongoing facilitator reflective practice requirements to reflect research-based approaches to preparing these leaders for intercultural communication, interprofessional engagement, and antiracist dialogue.

Mio and James both continue to strive toward the program’s mission: to bring together UMB students and post-doctoral fellows to critically reflect on issues of global and local importance while exploring orientations to communication in facilitated interpersonal and interprofessional groups, deepening and expanding engagement across perspectives of professional, disciplinary, and individual identity.

Moving Forward

Given its history, mission, and contemporary efforts to create conditions for meaningful conversation around professional and social issues and identities, Global Perspectives Conversation Program foremost remains a work in progress that responds to changes effecting the communities of participants. Mio and James recognize, therefore, that we must hold ourselves, as well as our approaches to planning, organizational mechanisms, and training curriculum, answerable to Black and Indigenous lives and the lives of people and communities of color that exist at the intersections of many racialized and minoritized identities. The ongoing work of this program focuses on standing with these communities in Baltimore and worldwide as they continue the resilient resistance to systemic white supremacy and violence. We know that answerability means reckoning with institutional, scholarly, and epistemic complicity in these forms of oppression by continuously revising the program’s framework to enact antiracist viewpoints and practices, including shaping space and opportunity for participants to critically and emotionally inquire about these changes and movements, as well as about the uncertainty and the intersections with their own lives and work in the academy.

Our strategy also includes structural action. We are negotiating ways to leverage the recent merger between the Office of International Services(OIS) and the Center for Global Education Initiatives (CGEI) to form the Center for Global Engagement (CGE). These newly combined resources offer the Global Perspectives Conversation Program a home base that reinforces local-global education efforts and extends opportunities to partner with the new UMB Intercultural Center and Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning. As we plan these new partnerships, we are engaging increasingly more faculty and student audiences about the potential scope and benefits of the Global Perspectives Conversation Program, as well as introducing and promoting related programs, including the International Student Peer Mentorship Program and the Volunteer Translator Program, both of which advocate for greater awareness of and justice for international students, perspectives, and language services. These programs in relationship with our partners form a bourgeoning network of support and, importantly, advocacy that insist on the fundamental global-local nature of social justice and antiracist work within and beyond the academy, centering the cross-border and myriad intersecting experiences and identities of all UMB students and scholars.