April 02, 2025 | Deborah Kotz

Individual Differences in How Brain Circuits Wired Provide Important New Clues

Nearly 16 million American adults have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but evidence suggests that more than 30 percent of them don’t respond well to stimulant medications like Ritalin and Adderall. A new clinical trial provides a surprising explanation for why this may be the case: There are individual differences in how our brains circuits are wired, including the chemical circuits responsible for memory and concentration, according to a new study co-led by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and performed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center.

Our brain cells have different types of chemical receptors that work together to produce optimal performance of brain function. Differences in the balance of these receptors can help explain who is likely to benefit from Ritalin and other stimulant medications. That is the finding of the new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal and funded by NIH.

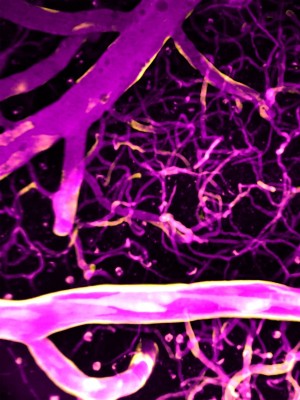

To conduct the trial, researchers conducted brain scans in 37 healthy adults without ADHD who performed concentration and memory tasks. The researchers used functional MRI scans to measure areas of brain activation during these tasks after the volunteers took a placebo on one day, and after they were given the drug Ritalin on a different day. They also performed PET scans to measure levels of the brain chemical dopamine and different types of dopamine receptors, which are involved in focus and concentration.

To conduct the trial, researchers conducted brain scans in 37 healthy adults without ADHD who performed concentration and memory tasks. The researchers used functional MRI scans to measure areas of brain activation during these tasks after the volunteers took a placebo on one day, and after they were given the drug Ritalin on a different day. They also performed PET scans to measure levels of the brain chemical dopamine and different types of dopamine receptors, which are involved in focus and concentration.

“We thought that the amount of dopamine Ritalin produced in a person would help us predict whether that individual would have enhanced attention performance, but what we found is more complicated,” said study co-corresponding author Peter Manza, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “Instead, we found the types of dopamine receptors on the brain cells, and the ratio in which they are found, better predicted cognitive performance.”

Study participants who had a higher ratio of D1-to-D2 brain dopamine receptors performed better on memory tasks during baseline testing compared to those who had a higher ratio of D2 receptors compared to D1 receptors.

“Balanced signaling between D1 receptors and D2 receptor in the brain is needed for optimal brain function and variations in their relative signaling contributes both to differences in baseline cognitive performance and to why some people improve whereas others deteriorate their performance when given Ritalin,” explained study co-corresponding author Nora Volkow, MD, chief of the Laboratory of Neuroimaging at NIH’s National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. “What we found was the those with a higher D2 to D1 ratio had worse baseline cognitive performance but experienced a greater improvement when taking Ritalin compared to a placebo.”

Interestingly, in the placebo session, those with a higher level of D1 receptors compared to D2 receptors tended to perform better on memory tasks with corresponding high levels of activation in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, as seen on functional MRI imaging scans. They did not, however, experience a significant improvement in their abilities after being administered either a placebo or Ritalin, even though Ritalin led to increased levels of dopamine.

“A significant number of people without ADHD are taking stimulant medications in an unprescribed way to try to increase their performance, and it was important for us to gain an understanding of what these medications were doing to the brain,” said Dr. Manza who is also a researcher at the UMSOM’s Kahlert Institute for Addiction Medicine. "Our findings suggest that many of these people may not benefit from taking these medications, while taking on the risks of using stimulant drugs without medical supervision."

The Kahlert Institute brings together leading addiction experts to collaborate and create the synergy necessary for systemic change. They include neuroscientists studying the brain mechanisms underlying addictions and physician educators working to train a new generation of medical students and residents

The Kahlert Institute brings together leading addiction experts to collaborate and create the synergy necessary for systemic change. They include neuroscientists studying the brain mechanisms underlying addictions and physician educators working to train a new generation of medical students and residents

Next on the researchers’ agenda: They would like to replicate the study on people who have been clinically diagnosed with ADHD to look at their D1/D2 receptor ratio and determine whether they tend to have a lower level of D1 receptors overall compared to those without the disorder.

“It would be interesting to identify whether there is a subgroup of individuals with ADHD who have high levels of D1 receptors and determine whether they are more likely to be treatment-resistant to stimulant drugs like Ritalin,” said Mark T. Gladwin, MD, the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore. “That could aid in our efforts to personalize care for these individuals and seek more beneficial treatments including cognitive behavioral therapies.”

Research reported in this press release was supported by NIH’s National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contact

Deborah Kotz

dkotz@som.umaryland.edu

Related stories

Tuesday, April 25, 2023

Immune System Sculpts Rat Brains During Development

Researchers have established that biological sex plays a role in determining an individual’s risk of brain disorders. For example, boys are more likely to be diagnosed with behavioral conditions like autism or attention deficit disorder, whereas women are more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders, depression, or migraines. However, experts do not fully understand how sex contributes to brain development, particularly in the context of these diseases. They think, in part, it may have something to do with the differing sizes of certain brain regions.

Friday, March 31, 2023

Traumatic Brain Injury Interferes with Immune System Cells’ Recycling Process in Brain Cells

Each year about 1.5 million people in the U.S. survive a traumatic brain injury due to a fall, car accident, or a sports injury, which can cause immediate and long-term disability.

Friday, January 06, 2023

UM School of Medicine Scientists Create First Extensive Brain Cell Data Repository

Neuroscience researchers now have access to 50 million brain cells to better understand how the brain develops and functions or changes with disease or trauma. Last month, scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s (UMSOM) Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS) unveiled a “one-stop shop” for brain cell data called the Neuroscience Multi-Omic Archive (NeMO Archive). This archive is now available to neuroscience researchers to transform their understanding of the complex workings of the brain.

Monday, November 14, 2022

Brain Area Thought to Impart Consciousness, Behaves Instead Like an Internet Router

Tucked underneath the brain’s outer, wrinkly cortex is a deeply mysterious area, known as the claustrum. This region has long been known to exchange signals with much of the cortex, which is responsible for higher reasoning and complex thought. Because of the claustrum’s extensive connections, the legendary scientist Francis Crick, PhD, of DNA-discovery fame, first postulated in 2005 that the claustrum is the seat of consciousness. In other words, the region of the brain enabling awareness of the world and ourselves.

Wednesday, February 02, 2022

ADHD Medicine May Treat Symptoms of Genetic Movement Disorder in Children, University of Maryland School of Medicine Study Finds

Using a common attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication appears to help manage the symptoms of a rare and currently difficult to treat genetic movement disorder primarily found in children, according to a new study from a University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researcher Andrea Meredith, PhD, and her collaborators.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

University of Maryland School of Medicine Study Finds Calcium Precisely Directs Blood Flow in the Brain

University of Maryland School of Medicine and University of Vermont researchers have shown how the brain communicates to blood vessels when in need of energy, and how these blood vessels respond by relaxing or constricting to direct blood flow to specific brain regions.

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Dr. Tracy Bale Elected President of the International Brain Research Organization

Tracy L. Bale, PhD, Professor of Pharmacology and Director of the Center for Epigentic Research in Child Health & Brain Development has been elected President of the International Brain Research Organization.

Monday, April 29, 2019

UMSOM’s Reading on the Brain Program Teaches Baltimore City Elementary Students About the Brain-Building Power of Reading

Acting Baltimore City Mayor Jack Young joined 4th and 5th grade students at Callaway Elementary School to help paint a mural about the brain. It was all part of Reading on the Brain, a University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) program to teach young students about the importance of reading and how reading can stimulate brain development and inspire future success. Tracy Bale, PhD, is leading the pilot program, which also emphasizes science and helps children to understand how the brain works.

Thursday, March 28, 2019

Allergic Reactions Play Role in Sexual Behavior Development in Unborn Males and Females, UMSOM Research Shows

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and colleagues at Ohio State University have discovered that allergic reactions trigger changes in brain behavior development in unborn males and females. This latest brain development discovery will ultimately help researchers better understand how neurological conditions can differ between men and women.

Friday, March 01, 2019

UMSOM Researchers Discover Clues to Brain Differences Between Males and Females

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have discovered a mechanism for how androgens -- male sex steroids -- sculpt brain development. The research, conducted by Margaret M. McCarthy, Ph.D., Professor of Pharmacology and Chair of the Department of Pharmacology, could ultimately help researchers understand behavioral development differences between males and females.

Thursday, December 07, 2017

University of Maryland School of Medicine Scientists Identify the First Brain Cells to Respond to Sound

Some expectant parents play classical music for their unborn babies, hoping to boost their children’s cognitive capacity. While some research supports a link between prenatal sound exposure and improved brain function, scientists had not identified any structures responsible for this link in the developing brain.