April 05, 2023 | Heide Aungst

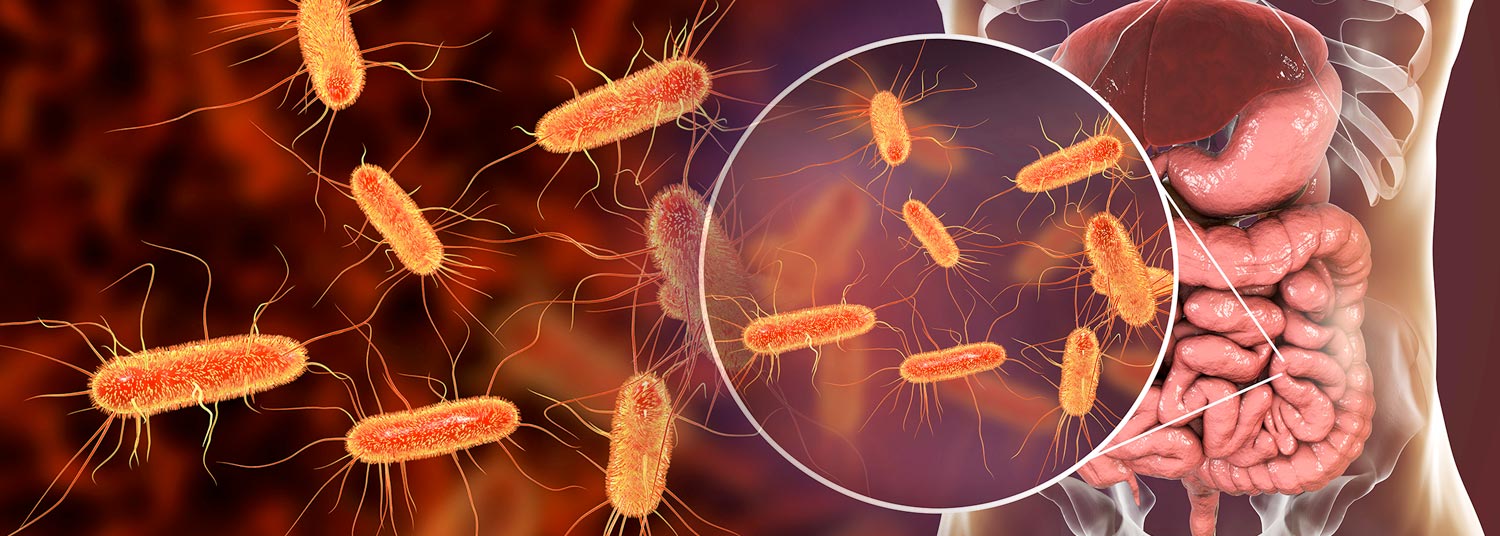

News reports featuring E. coli often tell terrifying stories of intestinal illness and diarrhea or deadly outbreaks from contaminated food. There are, however, many different strains of the bacteria E. coli, or Escherichia coli, and not all are bad.

Some E. coli may, in fact, play a key role in protecting the human gastrointestinal tract from severe illness, discovered researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s (UMSOM) Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS). Their work was published in a March issue of Nature Communications.

Some E. coli may, in fact, play a key role in protecting the human gastrointestinal tract from severe illness, discovered researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s (UMSOM) Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS). Their work was published in a March issue of Nature Communications.

“E. coli is a natural and common part of a healthy gut microbiome. Yet, most studies focus on the isolates that cause diarrheal disease,” said study corresponding author David Rasko, PhD, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at UMSOM, and a Scientist at IGS. “With our study, we wanted to examine what role the non-pathogenic E. coli plays. Could it be protective against illness?”

The researchers used data from E. coli strains from a group of 300 boys and girls under the age of five from countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia. The study that provided the strains — the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) was administered through UMSOM’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health — was a three-year case-controlled investigation of the causes of diarrhea (bacteria, viruses, and parasites) among children. The genomic data of the E. coli strains from children with and without diarrhea were examined to identify differences that may have caused the clinical outcomes. It is rare to have strains from healthy individuals to examine.

“We found these strains were more closely related to the dangerous E. coli strains than we expected, causing us to hypothesize that they may play a protective role in the gut, essentially by blocking out their disease-causing relatives,” said Tracy Hazen, PhD, Assistant Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at UMSOM, an IGS researcher, and lead author on the study. “We were surprised by the genetic diversity among the non-diarrhea E. coli causing strains.”

“We found these strains were more closely related to the dangerous E. coli strains than we expected, causing us to hypothesize that they may play a protective role in the gut, essentially by blocking out their disease-causing relatives,” said Tracy Hazen, PhD, Assistant Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at UMSOM, an IGS researcher, and lead author on the study. “We were surprised by the genetic diversity among the non-diarrhea E. coli causing strains.”

Another important finding in the study was that the E. coli within the children with diarrhea had significantly more antimicrobial resistance genes compared to the strains from children without diarrhea. The prevalence of bacteria with these antimicrobial resistance genes also means that there is a reservoir of these genes to be distributed to other E. coli and gastrointestinal bacteria, possibly making them even more resistant to treatment.

“This suggests that there is a dynamic relationship between the strains that may shift over time depending on what happens with the host immune response and the interaction with the microbiome — in this case, within the child’s gut,” Dr. Rasko explained.

With the observed genetic similarities of the strains, the researchers acknowledge that this poses a chicken-and-egg question: Do ‘good’ E. coli have the potential to evolve into the strains that cause illness? Or, did they start out as pathogenic strains that evolved protective qualities?

With the observed genetic similarities of the strains, the researchers acknowledge that this poses a chicken-and-egg question: Do ‘good’ E. coli have the potential to evolve into the strains that cause illness? Or, did they start out as pathogenic strains that evolved protective qualities?

Answering that question could lead to potential treatments for diarrheal diseases.

“Multiple studies have demonstrated that E. coli is present in the gastrointestinal tracts of 60 to 90 percent of healthy humans and can be considered cornerstones of the microbiome,” said UMSOM Dean Mark T. Gladwin, MD, Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor. "But we have not understood until now why something that can be so harmful to some people exists in the gut of healthy people."

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Now in its third century, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world — with 46 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs, and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished two-time winner of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1.3 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic, and clinically based care for nearly 2 million patients each year. The School of Medicine has nearly $600 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total population of nearly 9,000 faculty and staff, including 2,500 students, trainees, residents, and fellows. The combined School of Medicine and Medical System (“University of Maryland Medicine”) has an annual budget of over $6 billion and an economic impact of nearly $20 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine, which ranks as the 8th highest among public medical schools in research productivity (according to the Association of American Medical Colleges profile) is an innovator in translational medicine, with 606 active patents and 52 start-up companies. In the latest U.S. News & World Report ranking of the Best Medical Schools, published in 2021, the UM School of Medicine is ranked #9 among the 92 public medical schools in the U.S., and in the top 15 percent (#27) of all 192 public and private U.S. medical schools. The School of Medicine works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu

About the Institute for Genome Sciences

The Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine has revolutionized genomic discoveries in medicine, agriculture, environmental science, and biodefense since its founding in 2007. IGS investigators research areas of genomics and the microbiome to better understand health and disease, including treatments, cures, and prevention. IGS is a leading center for major biological initiatives currently underway including the NIH-funded Human Microbiome Project (HMP) and the NIAID-sponsored Genomic Center for Infectious Diseases (GCID). Follow us on Twitter @GenomeScience.

Contact

Heide Aungst

HAungst@som.umaryland.edu

216-970-5773 (cell)

Related stories

Wednesday, July 19, 2023

New Innovation in CAR T-Cells Paves Way for Less Toxic Therapy Against Multiple Myeloma

University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers engineered a new type of CAR T-cell therapy that, in preclinical studies, selectively attacked cancer cells while sparing healthy cells, potentially reducing the likelihood of toxic side effects from this innovative cancer treatment. The cells were designed specifically to attack multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells found in the body’s bone marrow.

Friday, July 29, 2022

Why Breast-Fed Premature Infants Have A Healthier Gut Than Formula-Fed Ones

Human breastmilk has long been considered “liquid gold” among clinicians treating premature infants in a newborn intensive care unit (NICU). Breastmilk-fed “preemies” are healthier, on average, than those fed formula. Why is that true, however, has remained a mystery.

Monday, September 20, 2021

UM School of Medicine Receives $7.5 Million Grant to Create Complex Model of Female Reproductive Tract to Study Infections

Researchers at the Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have received a $7.5 million federal grant to create a complex model of the female reproductive system in order to study sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They plan to create a realistic 3D model that integrates vaginal and cervical epithelial cells and the bacteria that colonize these cells, called a microbiome. They aim to use this model to identity factors that play a role in chlamydia and gonorrhea infections experienced by a growing number of women in the U.S. and worldwide.

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

UM School of Medicine Researchers Receive Federal Funding to Rapidly Test New Treatments for COVID-19

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) will be partnering on an agreement funded by the federal government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to rapidly test hundreds of drugs, approved and marketed for other conditions, to see whether any can be repurposed to prevent or treat COVID-19. The compounds will be tested in studies using state-of-the-art technologies in the laboratory of coronavirus researcher Matthew Frieman, PhD., Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. UMSOM will receive up to $3.6 million over the next year to fund this effort.

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

UMSOM Scientists Identify Key Factors that Help Microbes Thrive in Harsh Environments

Three new studies by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) scientists have identified key factors that help microbes survive in harsh environments.

Monday, February 08, 2016

UM SOM Researchers Identify Most Dangerous Strains of Often-Deadly Bacteria

A multi-disciplinary group of researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) have for the first time determined the genetic makeup of various strains of E. coli, which every year kills hundreds of thousands of people around the world.