February 02, 2022 | Cooper Roache

Common ADHD medication may provide insight into other ways to treat this and other neuromuscular diseases

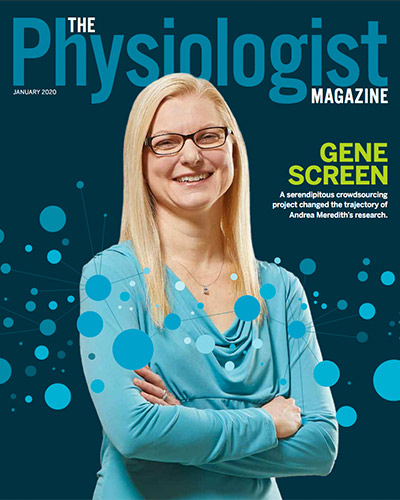

Using a common attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication appears to help manage the symptoms of a rare and currently difficult to treat genetic movement disorder primarily found in children, according to a new study from a University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researcher Andrea Meredith, PhD, and her collaborators.

The disorder, KCNMA1-linked channelopathy, named after the affected gene, can cause abnormal, involuntary movements from collapsing episodes, in which patients slump forward with their arms and legs appearing rigid. These episodes can occur up to 300 times per day, putting patients at risk of serious injury.

The researcher found that the stimulant drug, lisdexamfetamine, reduced these attacks and may help other accompanying symptoms, such as seizures and developmental delays, as well.

These findings were published online on December 11, 2021 in Movement Disorders Clinical Practice.

The researchers say their findings can help to better understand different brain regions involved with the attacks and how the disease manifests itself. While this research shows promise of specifically treating KCNMA1-linked channelopathy, there are broader implications to exploring the treatment effects on the body, potentially shedding light on the mechanisms behind other neuromuscular diseases and how to treat them.

“Sometimes the science doesn’t initially lead us to the answers, it is often the patients and families themselves,” said senior author Dr. Meredith, Professor of Physiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“Sometimes the science doesn’t initially lead us to the answers, it is often the patients and families themselves,” said senior author Dr. Meredith, Professor of Physiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Only about 75 people so far have been identified worldwide with this disorder which was identified as recently as 2005. A major advance came in 2019 when it was reported anecdotally that a child suffering from the disorder was prescribed lisdexamfetamine by their neurologist, which according to the family seemed to help. The physician tried this stimulant medication, commonly used to treat cataplexy-related disorders; the child’s symptoms resembled cataplexy, which is a sudden muscle weakness without losing consciousness. From there, word spread to other families over social media, news media, and the disease’s advocacy foundation, KCNMA1 Channelopathy International Advocacy Foundation, that was co-founded by Dr. Meredith. The buzz from the patients’ families spurred neurologists, including the study authors, to test the relatively safe drug that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat ADHD.

For their study, the researchers analyzed reports of six patients treated with lisdexamfetamine. They found that the collapsing episodes were reduced by about 10-fold or were completely resolved in four patients. Most patients also showed improvements in speech, school performance, concentration, and social skills, all of which can affect patients with this disease as well. None of the patients experienced seizures during the study period. The most common side effect reported was loss of appetite and difficulty sleeping.

“From the anecdotal reports we already had, we weren’t particularly surprised by these findings,” said Dr. Meredith. “But gathering the real-world evidence that the drug is actually working to treat the symptoms is important for clinicians who may prescribe the drug to officially diagnosed patients.”

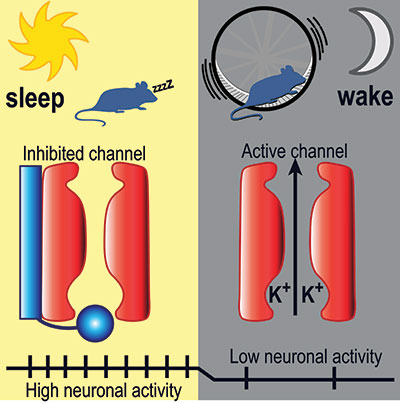

It is currently unclear how lisdexamfetamine works to treat the attacks. The gene affected in the disorder, KCNMA1, encodes a protein that makes a ‘channel’ in brain and muscle cells. This channel lets potassium out of the cell to change its electric charge. Neurons in the brain send messages and tell the muscles to move using these electrical signals, but the exact way this channel disruption leads to the symptoms experienced by the patients is unknown.

However, the success of lisdexamfetamine treatment in the small group of patients may provide the answers. “We have exciting mechanistic avenues to pursue as a result of this finding,” said Dr. Meredith. “We do know that the drug does not directly affect the activity of the channels, so we think the drug has either a separate, or an indirect effect, on the channels.”

They researchers plan to continue studies of the disorder and the drug in their mouse models.

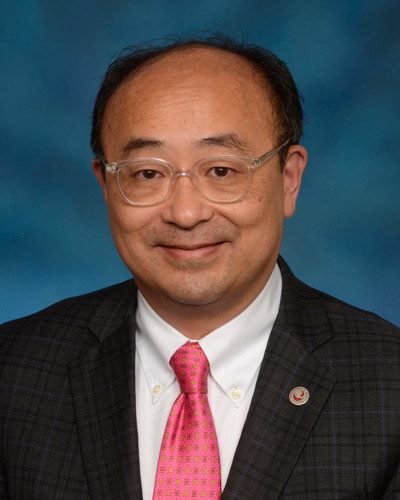

“Rare diseases are often overlooked in research and treatment ,” said E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs, UM Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean, University of Maryland School of Medicine. "We are proud of our researchers in pursuing treatment of a rare disease that opens new doors, pushes medical boundaries, and improves the lives of those who may feel left behind.”

“Rare diseases are often overlooked in research and treatment ,” said E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs, UM Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean, University of Maryland School of Medicine. "We are proud of our researchers in pursuing treatment of a rare disease that opens new doors, pushes medical boundaries, and improves the lives of those who may feel left behind.”

Other authors on the study included Sotirios Keros, MD, PhD, and Zach Grinspan, MD, MS, of Weill Cornell Medical College; Jennifer Heim, MD, Wejdan Hakami, and Michael Kruer, MD, of Phoenix Children's Hospital; and Efrat Zohar-Dayan and Bruria Ben-Zeev, MD, of Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Israel.

Dr. Meredith’s research is supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL102758), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32-GM008181), and the S&R Foundation Ryuji Ueno Award for Ion Channels Research (The American Physiological Society).

Dr. Keros, Dr. Meredith, and Dr. Kruer are uncompensated officers of the non-profit KCNMA1 Channelopathy International Advocacy Foundation. The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Now in its third century, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world -- with 46 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs, and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished two-time winner of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1.2 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic and clinically based care for nearly 2 million patients each year. The School of Medicine has nearly $600 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total population of nearly 9,000 faculty and staff, including 2,500 students, trainees, residents, and fellows. The combined School of Medicine and Medical System (“University of Maryland Medicine”) has an annual budget of over $6 billion and an economic impact of nearly $20 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine, which ranks as the 8th highest among public medical schools in research productivity (according to the Association of American Medical Colleges profile) is an innovator in translational medicine, with 606 active patents and 52 start-up companies. In the latest U.S. News & World Report ranking of the Best Medical Schools, published in 2021, the UM School of Medicine is ranked #9 among the 92 public medical schools in the U.S., and in the top 15 percent (#27) of all 192 public and private U.S. medical schools. The School of Medicine works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu

Contact

Vanessa McMains

Director, Media & Public Affairs

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Institute of Human Virology

vmcmains@ihv.umaryland.edu

Cell: 443-875-6099

Related stories

Wednesday, April 02, 2025

Researchers Reveal Key Brain Differences to Explain Why Ritalin Helps Improve Focus in Some More Than Others

Nearly 16 million American adults have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but evidence suggests that more than 30 percent of them don’t respond well to stimulant medications like Ritalin and Adderall. A new clinical trial provides a surprising explanation for why this may be the case: There are individual differences in how our brains circuits are wired, including the chemical circuits responsible for memory and concentration, according to a new study co-led by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and performed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center.

Wednesday, May 10, 2023

Research Identifies New Cause of Heart Failure Condition in Children

In an effort to determine the cause behind a rare condition that causes heart failure in children, University of Maryland School of Medicine researchers have identified new gene mutations responsible for the disorder in an infant patient. They were then able to learn how the mutation works and used a drug to reverse its effects in heart muscle cells derived from stem cells from the patient.

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Special Vascular Cells Adjust Blood Flow in Brain Capillaries Based on Local Energy Needs

When we smell hot dogs, it may trigger memories of backyard barbeques or attending baseball games during childhood. During this process, the areas of the brain that control smell and long-term memory are rapidly firing off impulses. To fuel these signals from neurons, the active brain regions need oxygen and energy in the form of blood sugar glucose, which is quickly delivered through blood vessels.

Wednesday, January 15, 2020

Dr. Andrea Meredith’s Research is the Cover Story in The Physiologist Magazine

One night just before bed in August 2018, Andrea Meredith, PhD, was reading the New York Times Magazine on her iPad when she came across an article about a six-year-old girl in South Dakota named Kamiyah who had a mysterious disorder. Over 300 times a day, the little girl would fall or slump forward, with large portions of her body paralyzed. An episode would last anywhere from three to 20 seconds. Then, suddenly, she would pop back up and resume whatever she was doing. The article mentioned that Kamiyah had paroxysmal dyskinesia, a type of movement disorder. But the cause was unknown.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

UM SOM Research Illuminates Key Aspects of How We Fall Asleep and Wake Up

Falling asleep and waking up are key transitions in everyone’s day. Millions of people have trouble with these transitions – they find it hard to fall asleep or stay asleep at night, and hard to stay awake during the day. Despite decades of research, how these transitions work – the neurobiological mechanics of our circadian rhythm – has remained largely a mystery to brain scientists.