August 04, 2020 | Deborah Kotz

Test Could Help Predict Risk of Metastasis

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) have developed a novel technology to test for the presence of thin membrane protrusions called “microtentacles” on breast cancer cells, which can help predict whether a tumor is likely to spread. They describe the TetherChip device in a new paper published today in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Lab on a Chip.

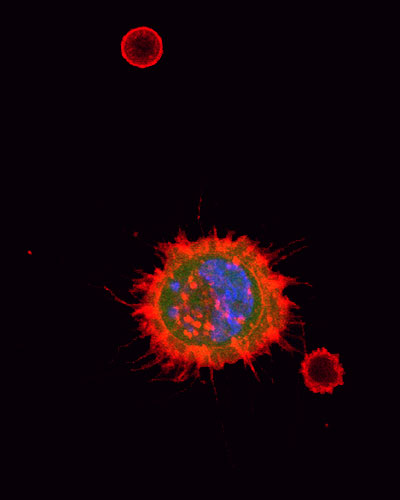

Microtentacles are thin membrane protrusions that extend from breast cancer cells and appear to play a key role in helping cancer cells spread from the original tumor and reattach themselves in distant organs. About 10 years ago, Stuart S. Martin, PhD, Professor of Physiology at UMSOM and his colleagues first identified and described microtentacles in breast cancer cells. They reported that a protein called “tau” promotes the formation of these microtentacles on breast tumor cells which break away from primary cancers and circulate in the bloodstream.

The research team, however, also encountered a persistent problem: Formaldehyde, typically used to chemically preserve cells taken from tissue biopsies, destroys the fragile structure of the microtentacles.

“In our new study, we describe our new solution for preserving tumor cells samples on a pathology slide without destroying the microtentacles they may contain,” said Dr. Martin who is the corresponding author of the new study with lead author Julia Ju. “Identifying and targeting these microtentacles on routine biopsies could be the next exciting frontier of cancer prognosis and treatment.”

The new research describes a tiny device filled with fluid called a TetherChip that is engineered to prevent cell adhesion (which would destroy any microtentacles) while also tethering the cell membrane to the device to immobilize the cell for better visualization under a microscope. TetherChips remain stable for more than 6 months and can be shipped across the country for patients seeking consultations with other oncologists. The samples can be rapidly fixed and stained on TetherChips, so patients can receive their biopsy results on the day of their procedure.

Dr. Martin, co-leader of the Hormone-Related Cancers Program at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, and his team collaborated with industry partners, Vortex Biosciences and ANGLE, to test whether the TetherChip could be used to analyze microtentacles on breast tumor cells isolated from blood samples. The companies had previously developed independent technologies to isolate live tumor cells from patient blood samples. The TetherChip technology has been licensed for further development by Cellth Systems, a Maryland-based company, with the goal of eventually seeking approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the device.

While this technology was developed to analyze breast tumor cells, the researchers also found that TetherChips allow for the analysis of multiple tumor cell types, which revealed for the first time that cancers beyond breast cancer can also form microtentacles.

“There are some potentially important clinical uses for this type of testing,” Dr. Martin said. “If we detect microtentacles, it might be better to choose a different form of therapy. Some forms of chemotherapy given before surgery to shrink tumors might actually increase the chances of these tumors spreading if the cells contain microtentacles.” Those patients may benefit more from immediate surgery to remove the tumor or from combination therapy with a drug that targets microtentacles for destruction.

Most chemotherapy drugs target cell division, aiming to slow or stop tumor growth. Dr. Martin said his team previously found that a popular chemotherapy drug, Taxol, actually causes cancer cell microtentacles to grow longer and allows tumor cells to reattach faster, which may have important treatment implications for breast cancer patients. They are currently investigating how other cancer drugs influence microtentacles in an effort to determine whether this test can be used to change clinical practice.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Veterans Administration, American Cancer Society, and the METAvivor Foundation.

“Determining the true role that microtentacles play in metastases remains an important avenue for research and could lead to important new advances in cancer treatment,” said E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs, UM Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean, University of Maryland School of Medicine. “This is adding an important piece to the cancer puzzle that could help explain why some tumors that shrink from chemotherapy remain so deadly.”

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Now in its third century, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world -- with 45 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs; and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished two-time winner of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1.2 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic, and clinically based care for nearly 2 million patients each year. The School of Medicine has more than $540 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total population of nearly 9,000 faculty and staff, including 2,500 student trainees, residents, and fellows. The combined School of Medicine and Medical System (“University of Maryland Medicine”) has an annual budget of nearly $6 billion and an economic impact more than $15 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine faculty, which ranks as the 8th highest among public medical schools in research productivity, is an innovator in translational medicine, with 600 active patents and 24 start-up companies. The School of Medicine works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu

About the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center

The University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Baltimore. The center is a joint entity of the University of Maryland Medical Center and University of Maryland School of Medicine. It offers a multidisciplinary approach to treating all types of cancer and has an active cancer research program. It is ranked among the top cancer programs in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. www.umgccc.org.

Contact

Contact:

Deborah Kotz

410-706-4255

dkotz@som.umaryland.edu