September 14, 2018

New Study to Focus on How Genetic Variation Affects Kidney Transplants

With African-Americans developing kidney failure at rates four to five times higher than Americans of European descent, a groundbreaking nationwide study will track nearly every African-American donor kidney over the next five years.

The study, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), will take place at 14 clinical centers across the country, one of which will be the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM).

The goal of the study is to follow every African-American donor kidney in every recipient of these kidneys over the next five years. In total, this will likely involve about 4,000 to 5,000 kidneys. The study, known as APOLLO, for APOL1 Long-term Kidney Transplantation Outcomes Network, is sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, which is part of the NIH. APOL1, which is short for Apolipoprotein L1, is a gene that appears to be different in many African-Americans, and may affect their rates of kidney disease.

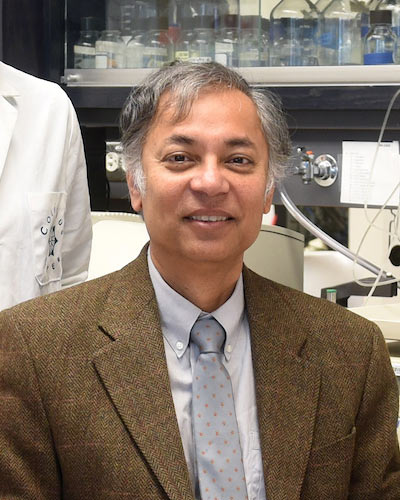

“A large part of the difference in rates may be genetic,” said Jonathan S. Bromberg, MD, PhD, a professor of surgery, microbiology and immunology at UMSOM. “In this study we hope to learn more about how genetics affects kidney disease and kidney transplants, and whether transplanted kidneys from people with this variant are more prone to rejection, or if these kidneys develop other problems such as increased scarring.” Dr. Bromberg, a transplant surgeon, is one of 14 principal investigators in the study and is in charge of the UMSOM portion.

Although African-Americans are 13 percent of the overall U.S. population, they make up more than a third of all patients receiving dialysis for kidney failure. African Americans and other people of African descent are much more likely to have a certain version of the APOL1 gene. The gene exists in only a few species in the primates. This genetic variant causes high rates of kidney disease. In Africa, the APOL1 variant had an evolutionary advantage: It protects against diseases caused by single-celled organisms called trypanosomes. In Africa, these diseases are common. One of them is sleeping sickness, which is transmitted by the tsetse fly. But the variant also appears to increase the risk of kidney damage. Researchers are now trying to understand more about the mechanisms behind this.

“This study will tell us much more about kidneys from African-Americans, both those that have the APOL1 variant and those that don’t,” said Dr. Bromberg. “This genetic variant was only recently discovered, and we have an enormous amount to learn about how it affects not only those who carry it, but people who receive kidneys from those who carry it.”

Over the next five years, the UMSOM site will likely perform about 100 kidney transplants involving African-Americans, and will follow and analyze these to find out everything they can about outcomes. In addition, Dr. Bromberg and his colleagues at UMSOM will follow and analyze a few hundred transplants of African-American kidneys done at other hospitals in the Baltimore-Washington area.

“Kidney disease and related illnesses remain a serious problem among African-Americans,” said UMSOM Dean E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor at UMSOM. “This important new research will help illuminate how kidney disease affects this population, and how this gene affects kidney transplant outcomes.”

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Commemorating its 211th Anniversary, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world -- with 43 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs; and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished recipient of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic and clinically-based care for more than 1.2 million patients each year. The School has over 2,500 students, residents, and fellows, and more than $520 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total workforce of nearly 7,000 individuals. The combined School and Medical System (“University of Maryland Medicine”) has an annual budget of nearly $6 billion and an economic impact in excess of $15 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine faculty, which ranks as the 8th-highest among public medical schools in research productivity, is an innovator in translational medicine, with 600 active patents and 24 start-up companies. The School works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu/

Contact

Office of Public Affairs

655 West Baltimore Street

Bressler Research Building 14-002

Baltimore, Maryland 21201-1559

Contact Media Relations

(410) 706-5260

Related stories

Monday, January 10, 2022

University of Maryland School of Medicine Faculty Scientists and Clinicians Perform Historic First Successful Transplant of Porcine Heart into Adult Human with End-Stage Heart Disease

In a first-of-its-kind surgery, a 57-year-old patient with terminal heart disease received a successful transplant of a genetically-modified pig heart and is still doing well three days later. It was the only currently available option for the patient. The historic surgery was conducted by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) faculty at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), together known as the University of Maryland Medicine.

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

University of Maryland Medicine to Eliminate Race from Kidney Function Estimates

University of Maryland Medicine, comprised of the University of Maryland Medical System (UMMS) and the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) has announced that it will end the use of a long-standing clinical standard that factors a patient’s race into the diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD). The change could increase access to specialty care, including eligibility for kidney transplantation for thousands of African American people living with advanced kidney disease.

Thursday, July 16, 2020

University of Maryland School of Medicine Recruits Two Preeminent Multi-Organ Transplant Professionals to Build on Legacy of Leadership in Transplantation

University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) Dean, E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, and Christine Lau, MD, MBA, The Dr. Robert W. Buxton Chair of Surgery at UMSOM, announced today the hiring of two internationally-renown transplant professionals: a surgeon scientist and a transplant scientist. The unique pair of transplant professionals provides UMSOM with a powerful combination of leadership in both clinical surgery and surgical science.

Friday, October 18, 2019

Diabetes Worsens Respiratory Illness Due to Abnormal Immune Response, UM School of Medicine Study Finds

Since the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) first emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012, there have been more than 2,400 confirmed cases of the infection, resulting in greater than 800 deaths – an alarming fatality rate of 35 percent. For this reason, researchers have been eager to identify any risk factors that contribute to the development of severe or lethal disease. Current clinical evidence points to diabetes as a major risk factor in addition to other comorbidities including kidney disease, heart disease, and lung disease.

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Researchers Identify How Vaginal Microbiome Can Elicit Resistance or Susceptibility to Chlamydia

The vaginal microbiome is believed to protect women against Chlamydia trachomatis, the etiological agent of the most prevalent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in developed countries. New research by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) shows how the microbiome can either protect or make a woman more susceptible to these serious infections.

Thursday, March 22, 2018

With Big Data, Researchers Identify New Targets for Lung Disease Treatments

Every year, approximately 12 million adults in the U.S. are diagnosed with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and 120,000 die from it. For people with COPD, Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium, can be particularly dangerous.

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

UMSOM Scientists Identify Key Factors that Help Microbes Thrive in Harsh Environments

Three new studies by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) scientists have identified key factors that help microbes survive in harsh environments.